Sexual exploitation (SE) is a very distressing subject. The scale of the issue is of international concern, affecting children, young people and vulnerable adults, both male and female. The National Working Group for Sexually Exploited Children and Young People (NWG) (2021) describes SE as occurring where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive people into sexual activity. This can potentially include people seen in a range of health contexts, so educating healthcare students using an interprofessional education (IPE) approach is essential, with the ultimate goal of learning and subsequently working together across professional boundaries (Department of Health, 2001). The international definition of human trafficking in the context of child SE is ‘the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a child, for the purpose of exploitation’ (NWG, 2021).

There have been many official inquiries in the UK, including the Jay (2014) inquiry, which estimated that 1400 children had been exploited in Rotherham over the 16-year period covered, the Derby Safeguarding Children Board (2013), Operation Yewtree (Gray and Watt, 2013) and, more recently, Operation Sanctuary (Spicer, 2018), which was conducted at the authors' study site, in Newcastle upon Tyne. Operation Sanctuary was set up in 2013 to investigate claims of sexual abuse against girls and young women, and discovered that 278 victims were involved. The findings of the inquiry resulted in the conviction of 18 people (17 men and 1 woman).

However, despite these figures, estimating the prevalence of SE remains challenging because, by its very nature, SE is not always easy to detect (Franklin, 2017). Identification of SE is exacerbated by the fact that some children do not necessarily recognise that they are being exploited, and so do not immediately seek help and support—for example, in cases involving children with a learning disability. Adults have a responsibility to protect children and it is unrealistic to expect those who are often unknowingly being sexually exploited to recognise this. Franklin (2017) argued that professionals' lack of awareness and knowledge of the indicators of SE can lead to the under-recognition and recording of sexual exploitation at a local level. Different local assessment processes can also exacerbate the difficulties in estimating the extent of SE on a national level. University graduates can seek work in any number of locations and so providing interprofessional learning opportunities around a global issue, and how to recognise it, was considered to be a central tenet of addressing the issue of SE through this educational initiative.

Safeguarding is concerned with protecting people's health, wellbeing and human rights. Section 10 of The Children Act 2004 emphasises that agencies must work together, providing justification for the decision to adopt an interprofessional approach in this study. The subject of safeguarding the public has always been included in undergraduate health student curricula because it is a requirement of professional bodies (Health Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2016; Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2018). Section 17 of the NMC Code (2018) stipulates that concerns must be raised immediately if a person is felt to be vulnerable or at risk of harm or abuse. To be inclusive, responsive and contemporary, the provision of education about SE is essential.

It is necessary to develop a culture of learning and continuous improvement to provide a flexible and responsive workforce with skills that are transferable across all care settings. IPE is concerned with student learning ‘about, from and with’ other professions (Barr and Norrie, 2010). In the context of SE, this hopefully results in joined-up interprofessional working practices, which can help early identification and lead to both prevention and detection. Healthcare students are encouraged to be vigilant and aware of the signs of any exploitation and are accustomed to having the subject of safeguarding embedded in their curricula. Focusing on a specific aspect of safeguarding had not previously been part of IPE, and an opportunity arose to develop SE material as part of an interprofessional module.

The aim of the study was to qualitatively assess student perceived impact of a novel IPE approach to delivering education about SE. This article reports on research that the authors designed, delivered and evaluated to develop an interprofessional community of learning, enabling the subject to be discussed with second-year undergraduate students. Participants were studying children's nursing, midwifery, adult nursing, occupational therapy, mental health nursing, physiotherapy and learning disability nursing. They will be registered practitioners within a year of completing this module.

Background

For some time, there have suggestions that training in sexuality and sexual issues should be part of the education of health professionals (Lawler, 1991; Haboubi and Lincoln, 2003). More recently, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) identified that there is a need for training to address knowledge and role clarity when working in the area of SE and suggested that training should address the ‘patchiness of professional knowledge’, as well as the need to ‘think qualifying curricula not just short course post qualifying training’ (Hackett et al, 2019). Taking into consideration the need for improved knowledge, recognition and barriers to reporting SE helped inform the design of the educational intervention.

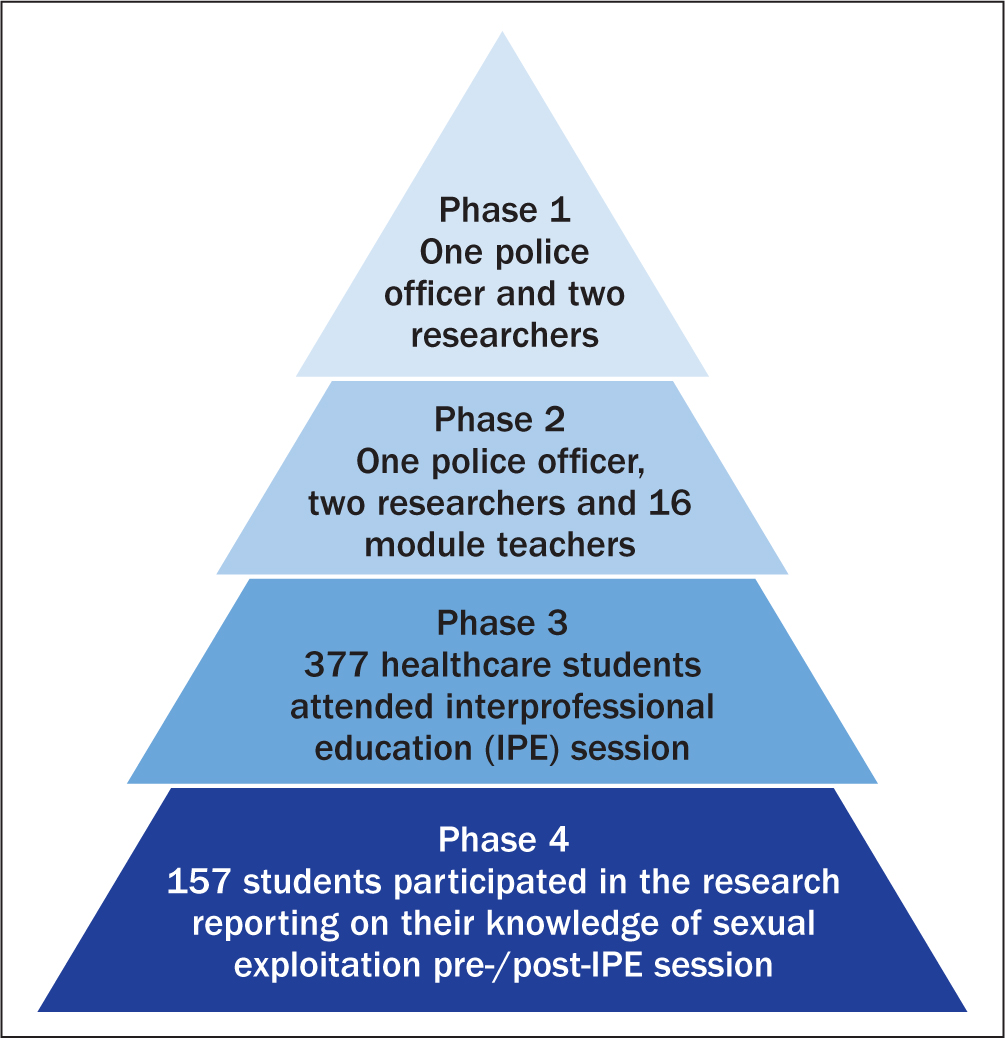

A phased approach (Figure 1) was adopted for the development of educational materials. It began with phase 1 consultation between the authors and the local police safeguarding unit, and subsequent consensus on the teaching content, both of which are important quality issues when developing shared IPE material (Bridges et al, 2011). The purpose of linking with the police was to learn about the approach adopted in training police officers on this subject and to adapt it for health students. Around the time the initiative was being developed, a local police investigation into SE was under way and the force had developed training materials for their officers. This contained information around models of SE, risk factors and how to recognise it. Discussion took place between the authors and the police and it was agreed that certain elements of police training material could be used and the police force's involvement acknowledged. They provided a DVD with a film clip with a service user's voice describing local locations where her SE took place. This element of the police training was felt by the authors to be authentic and invaluable learning for the students, some of whom recognised the locations in the film. The content of the police material appeared to map closely against government guidance from the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF), (2009)—now the Department for Education (DfE)—so the authors proceeded to consolidate the relevant components of information into an educational package that included directed learning and seminar materials, and had five learning outcomes. More recent government guidance on child SE includes:

- What to do if you're worried a child is being abused: advice for practitioners (DfE, 2015)

- Child sexual exploitation: definition and guide for practitioners (DfE, 2017)

- Working together to safeguard children (DfE, 2018).

Figure 1. Chronology of development of sexual exploitation educational materials

Figure 1. Chronology of development of sexual exploitation educational materials

Johns (1995) highlighted Carper's ‘ways of knowing’ in nursing, which explore how students may respond to a particular clinical situation (aesthetics), as well as understand the right and wrong ways to take action (ethics). It could be argued that these two ways link well to learning about the subject of SE, where clinical skills and ethical decision-making are key. Oakeshott (1991) described two types of competence, making a clear distinction between ‘knowledge-based competence’ and ‘technical-based competence’. The authors wanted the students to ‘know what’ around SE, as well as ‘know how’, at the same time, by developing their theoretical and practice-based knowledge. The five learning outcomes (LOs), defined before the teaching took place, aimed to ensure students:

- Know how to identify signs of SE in children, young people or adults (LO1)

- Appreciate various models of exploitation (LO2)

- Consider signs of trafficking (LO3)

- Understand issues around SE and the legal framework (LO4)

- Apply safeguarding principles and consider the role of the health professional (LO5).

Once the material was developed, the staff delivering the teaching were invited by the authors to ‘test drive’ it, and participate in discussion (phase 2); the police were also invited to participate in the test drive. Teaching staff could preview the material, which included quizzes, Powerpoint slides and film footage, and they were also able to informally discuss/challenge the content with the developers, offering suggestions and amendments. According to the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (2014), consideration should be given to staff delivering such sessions: some may see this as an area that is outside their usual remit and will need to gain confidence, as well as competence, in teaching such material. Some of the staff expressed uncertainty about the potential for student distress due to the nature of the subject matter, while other staff sought validation of facts from the police due to a degree of disbelief. They were assured that information on support would be available at the start of the session and at the conclusion of the Powerpoint presentation, which would include telephone numbers of organisations to contact should any students or teaching staff need additional support.

Finally, once the staff had been briefed and the teaching materials agreed, the information was electronically posted for students, with an alert linking to the SE self-directed learning. The 2-hour workshop included:

- Self-directed study in the form of a learning package, completed in advance of the timetabled session

- Information on signs and indicators, and a Powerpoint presentation on models of SE

- A quiz focusing on sexual exploitation issues, and IP group discussion based on the prior e-learning on SE.

- An extract from a DVD from Northumbria Police centred on a young person's experience of SE.

This pedagogical approach of blended and face-to-face learning offered students maximum opportunity to interact and discuss issues within their interprofessional groups. About 24 students took part in each education session, who were then allocated to interprofessional subgroups to mix the disciplines. At the timetabled seminar, all students (n=377) were invited to participate in the research (phase 3) and to evaluate their knowledge before and after the session. A total of 157 students participated on the day (phase 4).

Methods

Research design

This study took place within Northumbria University. University ethical approval was gained. A qualitative approach was adopted using semistructured questionnaires for self-reporting on pre- and post-intervention by students from seven professional groups studying the second-year IPE module.

In advance of the study students were emailed a participant information sheet. They were assured that their anonymity would be preserved and they were advised that support would be provided in the event of anyone experiencing distress following the session, in the form of student support services and national helpline contact numbers. This is an important consideration: according to Lowe and Jones (2010), it is essential to have support measures in place when teaching distressing subjects of this nature. Student who agreed to participate completed a consent form on the day of their timetabled session.

Data to elicit each student's levels of knowledge before and after the workshop were collected during the IPE session using before and after feedback sheets consisting of semistructured questionnaires, filled in by hand. This method was selected because it was considered more likely to encourage students to be open, reflective and candid in their reporting on a sensitive subject, hopefully leading to deeper learning.

The 157 students who consented to participate were spread across the specialities as follows: children's nursing (n=15), midwifery (n=12), adult nursing (n=60), occupational therapy (n=14), mental health nursing (n=20), physiotherapy (n=25), and learning disability nursing (n=11) (Table 1).

Table 1. Interprofessional student teaching groups

| Teaching groups/specialty | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 5, 6, 7, 8 | 9, 10, 11, 12 | 13, 14, 15, 16 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children's nursing | ✓ | 15 | |||

| Midwifery | ✓ | 12 | |||

| Adult nursing | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 60 |

| Occupational therapy | ✓ | 14 | |||

| Mental health nursing | ✓ | ✓ | 20 | ||

| Physiotherapy | ✓ | 25 | |||

| Learning disability nursing | ✓ | 11 | |||

| Total | 51 | 40 | 29 | 37 | 157 |

The table show the group mix across disciplines, for example teaching group 1, 2, 3 and 4 included students from learning disability (n=11), children's nursing (n=15), mental health (n=10) and adult nursing (n=15)

Data analysis

The feedback forms were initially read and discussed by the authors, and an initial coding frame agreed (Braun and Clark, 2006). The authors began by coding the data independently, then came together to seek consensus on the emergent themes (Table 2). The themes were then applied to each set of ‘before’ and ‘after’ feedback sheets. A data workshop was held with both authors and an independent external researcher to identify, refine and agree final themes, as well as to provide rigour for the study.

Table 2. Themes that emerged from the data analysis

| Teaching groups | Knowledge before teaching session | Knowledge after teaching session |

|---|---|---|

| 1, 2, 3, 4 |

|

|

| 5, 6, 7, 8 |

|

|

| 9, 10, 11, 12 |

|

|

| 13, 14, 15, 16 |

|

|

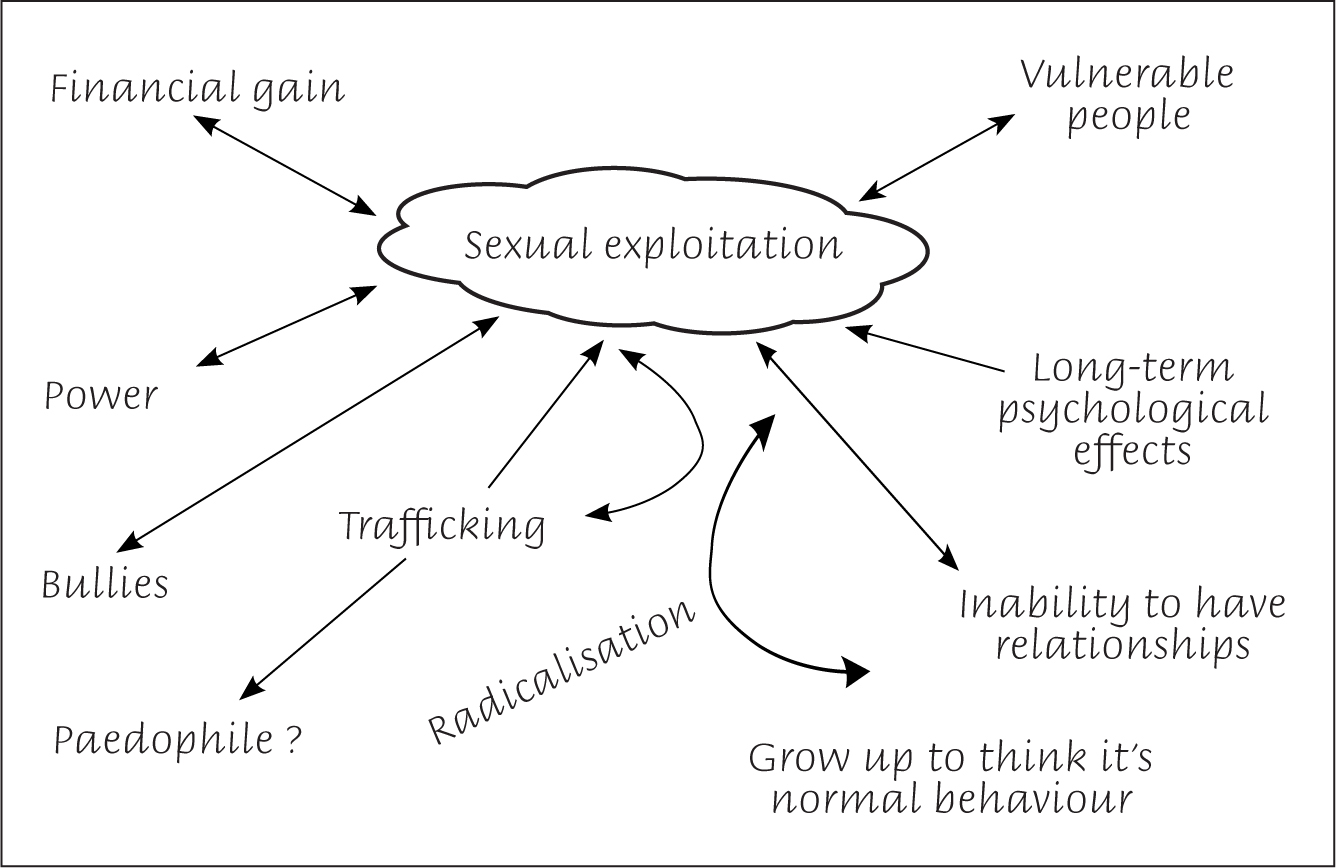

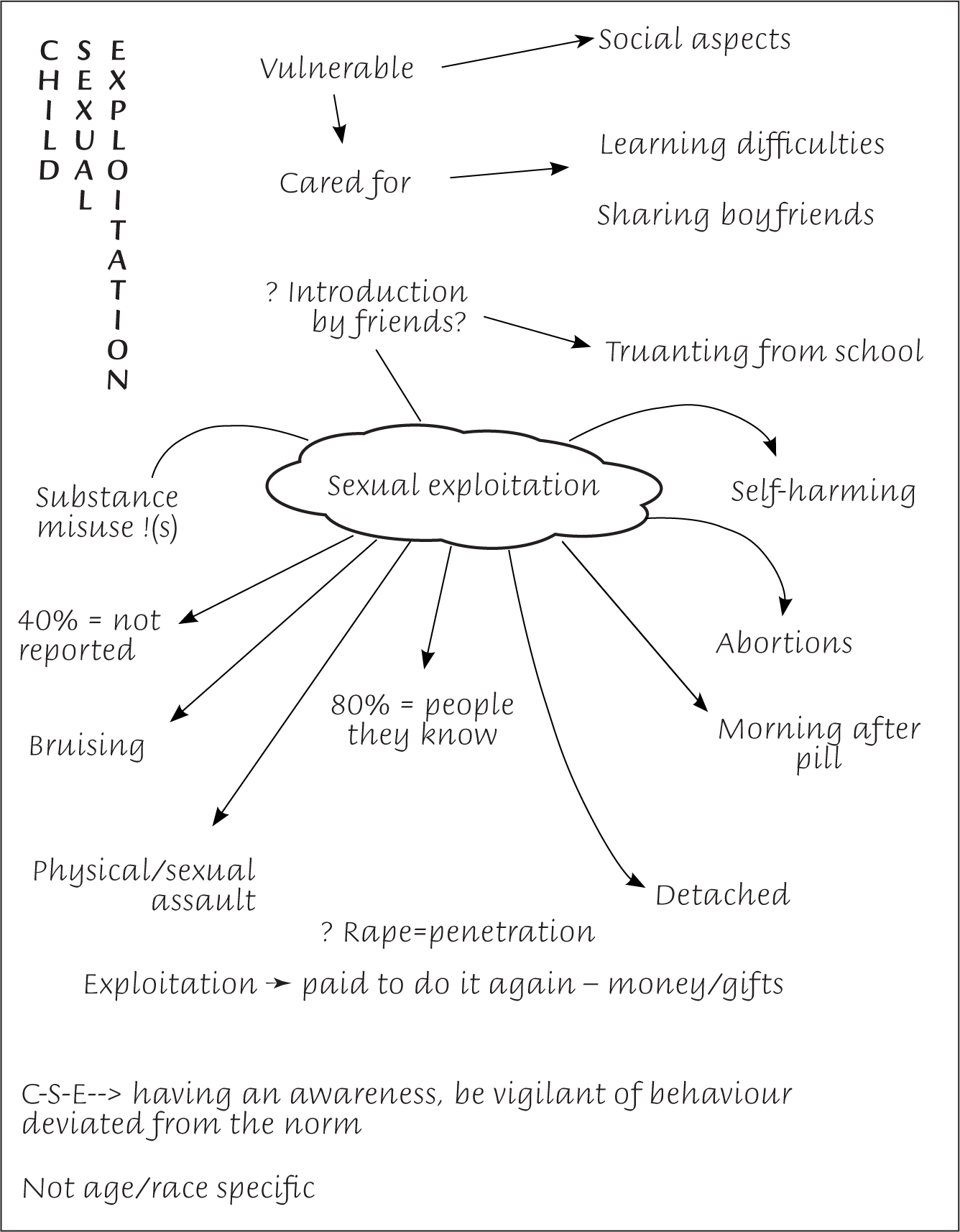

The emergent themes were written onto A1-size flipcharts to identify the broad themes from before and after the workshop. Figure 2 represents one student's perspective of SE knowledge prior to the session—the independent external researcher assisted in analysing this example of visual data. It indicates some level of insight/knowledge, linked to a small number of concepts that are common knowledge and very broad. In contrast, Figure 3 shows a more professional detailed and nuanced understanding. The student has indicated more specific new knowledge, for example around statistics, as well as a heightened awareness and need to be vigilant around changes in the behaviour of some young people.

Figure 2. An example of one student's visual representation of knowledge prior to the interprofessional session

Figure 2. An example of one student's visual representation of knowledge prior to the interprofessional session  Figure 3. An example of the same student's (see Figure 2) visual representation of new knowledge post-interprofessional session

Figure 3. An example of the same student's (see Figure 2) visual representation of new knowledge post-interprofessional session

Results

Student knowledge prior to participation

The students from the adult nursing specialty were well represented (n=60) in each teaching group session (Table 1). Their feedback showed that they had had little knowledge of the subject prior to the teaching session, and thought that SE occurred mostly outside the UK, organised predominantly by ‘controlling adults’, with no consent given. The adult nursing students commented that their knowledge came mainly through social media: for example, one thing they had learnt from social media was that gifts could be exchanged in return for sex. They also commented that they thought that people with learning disabilities/intellectual disabilities were at greater risk of SE.

The midwifery students (n=12) thought that they had had a ‘vague idea’ about SE, and that it involved power and bullying by perpetrators. The children's nursing students (n=15) reported having limited knowledge, but thought that poor school attendance and changes in usual behaviour could be features of SE. Students from the least represented group, learning/intellectual disability nursing (n=11), reported that their knowledge had stemmed mainly from media coverage and television programmes. This group observed that sexualised behaviour in clients could be an indicator of exploitation. The mental health nursing students (n=20) noted that some clients might find it difficult to realise that they were being exploited and that the internet is ‘an avenue for recruitment’. They reported that gifts and ‘substances’ could be used to ‘groom’ individuals. They acknowledged they need to ‘broaden’ their knowledge. The issue of imbalance of power between perpetrator and victim was acknowledged by the mental health nurses, as well as the development of an ‘abusive relationship’. They acknowledged that SE could happen to anyone of ‘any age, gender or race’.

The occupational therapy students (n=14) cited the internet as a medium for exploitation, especially of children. The area of SE was felt by another group to be more the provenance of the police and social services departments, rather than health professionals. The physiotherapy student (n=25) did not know how to report concerns about abuse or exploitation, however, they thought that they were in ‘a pivotal position to notice signs and act on these’, according to feedback from one of the physiotherapy students.

Results

Student knowledge following participation

Teaching groups 1-4: adult, learning disability, children's and mental health nursing

This interprofessional group reported on several aspects following the IPE session. They remarked on how the session had made a ‘difficult subject easy to learn’ and it had been informative; they also commented that it was ‘scary to think what actually happens’ in SE. They highlighted increased levels of knowledge of the effects of SE and that they now knew that it was a highly organised and networked operation.

The group thought professional curiosity was essential and after the session they felt they would be able to speak up and feel supported in doing so. They highlighted their new knowledge of trafficking (‘it can be town to town, not necessarily overseas’), as well as about existing and emerging models of SE. The importance of speaking up and voicing concerns was highlighted, even if there was a risk of ‘getting it wrong’. They noted how other professionals may unwittingly exclude the possibility of SE when carrying out assessments of physical and/or behavioural changes in children and young people.

These students also thought they now knew more about documents to complete and forward to other services, how to report SE and policies. Some made links to the government's counter-terrorism strategy CONTEST (Home Office, 2018), which had been taught in a different lecture. The students made connections to the government's Prevent strategy and how to protect vulnerable people (Home Office, 2018). This group also cited their understanding around age of consent; they also said that they had gained knowledge about how exploitation could occur and that it could happen to anyone, but especially vulnerable people and children. This interprofessional group now appreciated that vulnerable people could be exploited through manipulation or coercion, without their understanding of what was happening.

Teaching groups 5-8: physiotherapy students and adult nursing students

These two student groups indicated that now that they had done the session, they felt better able to spot the person at risk of SE and felt more confident at ‘protecting’ them and referring to safeguarding teams. Health professionals have regular contact with the public and the students acknowledged that ‘victims’ do not explicitly ask for help. The students also noted that ‘huge numbers’ do not report it and that there are a number of different models of SE.

According to Milligan et al (2017), physiotherapy students are used to employing prompts/mechanisms to anticipate what to do in a given clinical situation. In evaluating the SE training, they reported that they now recognised that, as students in the clinical setting, they had real opportunities to raise concerns immediately, if they had any suspicions. They seemed to feel that there would be scope for more authentic practice learning to take place in future in those work environments where they would have more autonomy.

Teaching groups 9-12: occupational therapy students and adult nursing students

Following the session, this group commented that they had gained knowledge about the warning signs, and knew to be observant for secretive behaviour, petty crimes, unexplained gifts and inappropriate behaviours. Additionally, they now understood that anyone is vulnerable, including boys. The group reported they had an improved awareness of SE following the session, and understood the need to be vigilant and whom to tell if they were concerned. The group identified the importance of using professional curiosity to look for and explore signs/changes in behaviour and to think about what may be causing this behaviour. The students highlighted the duty that, as health professionals, they needed to look out for risks. They also said that it was ‘unacceptable not to act on clues we come across them in the course of our career or even training placement’.

Teaching groups 13-16: midwifery, mental health and adult nursing students

This group commented on the importance of recognising indicators of SE and thought that it was very relevant for them to be aware of these them as professionals. After the session, they reported being more aware about the extent of the problem and felt able to speak up. They also understood they would be supported in doing so because they had ‘learnt more about documents/policies and how to report’ SE. Their knowledge had been deepened, including about the prevalence of SE and the fact that some victims were aware that they were being groomed. The session encouraged these students to think about SE more holistically, with knowledge about the professionals' roles in helping young victims of SE, for example, referring them to mental health staff and other professionals with whom they may not work on a daily basis. Comments included that ‘an understanding has developed about estimated statistics’, as well as an appreciation of ‘how challenging it can be to overcome other professionals' attitudes’.

Discussion

Pre-session knowledge

Before taking part in the session, students described their views and knowledge through their uni-professional lenses, acknowledging that they had little knowledge of SE and that what they did know came mostly from the media. They appeared to appreciate that people with intellectual disabilities were more vulnerable, but also that anyone could experience SE. One of the uni-professional groups indicated that they thought SE was not a matter for health personnel—they thought it was mainly the remit of social services and law enforcement bodies.

Post-session knowledge

The comments following the IPE session mainly related to changes in their knowledge and understanding, and acknowledging the fact that they came from different professional and personal backgrounds. An overarching theme that emerged in our study was that before the session all students had little or no prior knowledge of SE, and had thought ‘it was other professionals' business’, which changed after participation to them gaining knowledge about SE and understanding the significance of their own ‘pivotal position’ as health professionals. In some of the interprofessional groups only two disciplines were represented, eg teaching groups 5-8 had adult nursing specialism and physiotherapy. This is acceptable: it is appropriate ‘when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’ (Bainbridge and Wood, 2012). In addition to the four nursing specialties, this study included midwifery, physiotherapy and occupational therapy students in the interprofessional mix.

There were comments in the post-session feedback that SE could be a highly organised and networked operation. Students stated that after taking part they knew more about document and policies, and had increased understanding around the age of consent. There was evidence that students were using knowledge gained around vulnerabilities from other parts of their degree programmes. There was a strong recurring theme throughout about acknowledging their roles as health professionals in spotting SE and referring to safeguarding authorities. Some noted that the session encouraged holistic thinking, which is endorsed in the document Working Together to Safeguard Children (DfE, 2018). In one section of the document, which was used as a resource, it describes itself as a ‘myth-busting guide to information sharing’ and highlights additional signs in children and young people that could indicate they may be vulnerable to SE.

Students commented that before taking part in their groups, they had not felt able to raise concerns unless they were sure there was an issue of concern, but they now felt confident in reporting suspicions even when uncertain. They justified having professional curiosity and felt more able to challenge other professionals, both as students and qualified practitioners. This is in line with guidance in the intercollegiate document on the roles and responsibilities of health professionals working in safeguarding (Royal College of Nursing (2019).

The authors were reassured to discover that the themes emerging from the post-training feedback identified increased knowledge around the models and signs of SE, and how to report it. The students stated that their awareness of the topic had been raised and they now understood why young people might become involved in SE, as well as the fact that anyone at any age can be vulnerable. They recognised that they need to stay alert in practice because, although victims do access health services, they may not state that their attendance is for SE-related issues. The need to use one's professional curiosity and ask about areas not in the students' usual remit, eg assumptions around school attendance, is vital.

The authors felt the interprofessional learning enabled this more collegiate approach to working together in practice. They were encouraged to see the students' appreciation of the strong evidence-based approach to the content, including statistics on prevalence, and new understanding of SE as an issue that they are all likely to encounter. From examining the themes closely, the authors felt that any barriers and challenges to safeguarding education had been successfully addressed through this educational initiative.

Educational process

Following the IPE session, there was evidence of transformative learning. Mezirow and Associates (1990) talked about critical reflection and perspective transformation. He argued that adulthood may be the time for reassessing assumptions of one's formative years that may have resulted in distorted views of reality. Some students may have thought that they were being asked to challenge their belief systems. Hence, one student's response was that ‘it is disgusting’ and another stated it was ‘scary to think what actually happens’. Bandura (1971), in discussing social learning theory, supported the notion that learning may also take place via unplanned experiences and at an unconscious level, for example, through observation and internalisation of the behaviour of another person. This may have led to some students, in their small IP subgroups, to reflect and alter their views on SE as a direct result of being in an interprofessional learning environment.

Outcomes of an affective nature enable students to embrace future learning, as well as changing attitudes and sets of values. This was evident in the author's study as highlighted by one student's comments after the session: ‘We all need to have professional curiosity’ and ‘We now know the warning signs and to follow safeguarding referral procedures even if we think we may be wrong’. Another stated that it is ‘unacceptable not to act on clues we come across it the course of our career or even training placement’. The classroom became, as Burns (1982) put it, a social learning environment, as well as a place for cognitive gain.

Students are diverse, with different experiences of their own to draw on and individual students may have had their own reasons for participating or not participating in the study. It is not certain whether refusals to participate were related to the sensitive topic, facilitator enthusiasm/engagement skills, student learning style, genuine non attendance on the day or simply a general lack of interest.

Pollard et al (2005) referred to ‘second-year scepticism’ and explored the, at times, ambivalent attitudes of students to interprofessional learning at the midpoint of their studies. SE is also an emotive and sensitive subject for facilitators to explore with students, and facilitators, according to Pollard et al's study, may have mixed levels of confidence in addressing the issue in a uni-professional setting, let alone in an interprofessional context. This could have subsequently resulted in the students in the authors' study possibly not feeling confident enough to self-report on knowledge gained.

However, in the authors' study, there was no evidence from student feedback to suggest that this was the case. Key to the success of this educational initiative was the effective preparation of the facilitators when they met to discuss the educational material in advance of delivering the session. This ensured that they were included, fully briefed and aware of the contemporary issue of SE. Interprofessional collaboration on preparing the education materials was the beginning of the process. The authors and the police had prepared the content, but recognised that, owing to the sensitivity of the subject matter, the need to prepare facilitators was integral to achieving the intended learning outcomes. Like the students, the facilitators had a range of different experiences and their own views on the subject. According to Freeth et al (2005), IPE makes different demands on educators for whom uniprofessional teaching may be the norm and IPE ‘can be uncomfortable for some’. In the case of IPE around the emotive subject of SE, an encouraging and supportive approach was taken in this study with the preparation of the facilitators. Steven et al (2007) considered that this is crucial when dealing with emotions and discussions around sensitive issues.

This article has attempted to fill the gap in demonstrating the effectiveness of an IPE initiative around SE. Participant feedback indicated an increased level of knowledge in relation to SE after participating, in particular, students identified that post-session they were better able to:

- Identify signs of SE in children young people or adults

- Appreciate various models of exploitation

- Consider signs of trafficking

- Understand issues around SE and the legal framework.

- Apply safeguarding principles and consider the role of the health professional.

Study limitations

In total, 377 students attended the teaching groups on SE and 157 consented to participate in the qualitative study. A limitation may have been not exploring further the reasons for non-participation. Information about the students' age was not requested and this may be a further limitation of the study. Anderson and Thorpe (2008) suggested that mature entrants value IPE and prefer more challenging learning resources. The students in this study were all undergraduates and appeared to be in a range of age groups, including some mature students with previous work experience in health care.

Gaining feedback from the facilitators delivering the sessions would have been informative and any relevant observations on their part could contribute to influencing the design and delivery of this innovative IPE approach.

Another limitation could be the challenges of collecting and analysing qualitative data obtained from a questionnaire, because there is a risk that this approach may have hindered the depth of responses, which may have otherwise been obtained through semi-structured interviews. These points could be incorporated into future research.

Conclusion

SE is a widespread international issue, with new cases regularly coming to light. The number of people affected cited have in some inquiries been more than 1500 (Jay, 2014). SE is serious issue that health professionals will encounter in a range of practice contexts, so it is essential that all health and allied health students are prepared through their education to recognise, report and help manage them. It has been highlighted that training in sexual issues should be part of undergraduate health curricula, and the professional regulators for nursing, midwifery and allied health professions state that safeguarding is a requirement for professional practice (HCPC, 2016; NMC, 2018). However, the NSPCC has suggested that there is a paucity of professional knowledge around the safeguarding aspects specific to SE (Hackett et al, 2019).

This study has indicated that the new IPE session on SE has had a positive impact on the knowledge of undergraduate healthcare students. The IPE nature of the delivery has had a significant influence on student learning. Following the study, the students who took part in the study reported an increased level of awareness, understanding and confidence about working with individuals affected SE. This IPE session has since been incorporated into the nursing, midwifery and allied health programme in a local university and is part of a second-year undergraduate module on knowledge and skills for safe practice.

It is important that this aspect of safeguarding is incorporated in healthcare curricula and should be accorded an equivalent status as traditional practice-based skills. This article has considered how future health practitioners are educated and has challenged the traditional means of healthcare education. The Health Professions Network Nursing and Midwifery Office (2010) described IPE as an opportunity not only to change the way educators think about preparing future health practitioners, but also an opportunity to step back and reconsider traditional methods of healthcare education.

Delivering effective IPE can encourage and support changes in educational practices, as well as changes in the culture of health care. The findings of the study have clearly highlighted that the context for interprofessional learning around SE is crucial, and the authors are confident that future practitioners who have taken part in IPE sessions on SE will make a difference to the lives of those who may be victims or vulnerable to SE.

KEY POINTS

- Before taking part, students felt sexual exploitation (SE) was not a matter for health and allied care professionals, but the remit of social services and law enforcement bodies. After participating, they understood that they are in a pivotal position to identify signs of SE and to take action

- Students realised that SE occurs ‘close to home’, that the numbers are ‘huge’, and they recognised that health and allied care professionals need to be more vigilant and professionally curious

- Successful interprofessional teaching and learning can contribute to knowledge of SE and the momentum should not be lost. It is crucial that CPD education includes SE to help protect vulnerable people at risk

- There is a need for CPD around SE to enable healthcare students to build on other content of their undergraduate programmes, providing a seamless continuum of professional knowledge around practice in this area

CPD reflective questions

- The article has shown how students from different specialties reacted to learning about sexual exploitation (SE). What do you think is the main benefit of interprofessional learning about the subject for health and allied care students and professionals?

- Do you think you have been equipped with the right skills to identify and support vulnerable or potentially at-risk patients? Could you raise the issue of learning about SE in your workplace with your managers?

- If you have undertaken any courses on SE, was this within a uni-professional environment? What would be the benefits and disadvantages of learning about SE with colleagues from the same or different specialties