In the UK, one-quarter of all deaths are caused by heart and circulatory diseases, and heart attacks account for more than 100 000 hospital admissions a year (British Heart Foundation, 2025). It has been estimated that 80% of premature heart attacks are preventable with correct risk-factor modification advice (Waterall, 2018). However, individuals living in highly deprived areas of England are almost four times as likely to suffer early death from coronary heart disease as those living in less deprived areas (Lomas and Williams, 2019).

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a combination of activities designed to improve health behaviours, reduce risk factors for coronary heart disease and help patients recommence life in their communities (British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR), 2023). CR is cost effective and has been shown to lower risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and cardiovascular risk factors at 1 year after a myocardial infarction (MI) (Shields et al, 2018; Eijsvogels et al, 2020; Sjölin et al, 2020; Dibben et al, 2021; 2023). The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020) guidance recommends that all patients who have had an MI should be offered CR and encouraged to attend. CR also increases functional capacity and has been linked to a reduction in hospitalisations for patients with heart failure and following heart valve surgery, but is underused in both these patient groups (Patel et al, 2019; Abraham et al, 2021; Bozkurt et al, 2021).

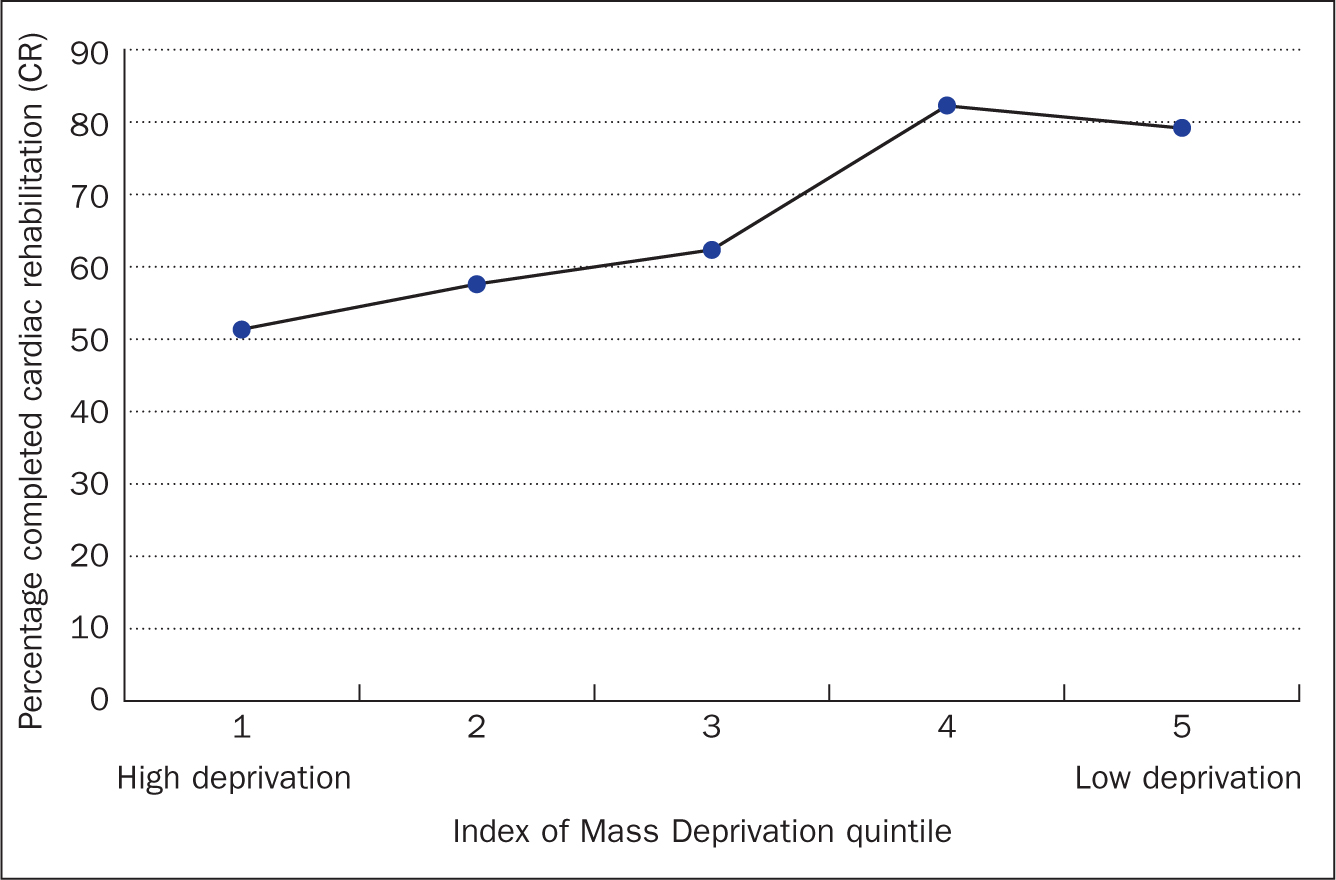

Areas of high deprivation are identified using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), which is formulated using seven traits including deprivation of income, employment, skills, training, and health - these domains are also referred to as the Indices of Deprivation (IoD) (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2019). The IMD is a relative measure and cannot be used to quantify deprivation or identify deprived people (Lam, 2019). Patient completion of CR in higher deprivation areas is lower than low deprivation areas – 40% versus 48%, according to data from the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation for the 2020/21 financial year (personal communication, 2024). This is not a new phenomenon, research from 1999 in Nottingham found level of deprivation was associated with CR attendance (Melville et al, 1999). Although CR programmes improve outcomes, the lack of their completion in areas of high deprivation suggests that the programmes could inadvertently contribute to widening existing health inequalities. Figure 1 illustrates the completion rates by IMD quintile in the Coventry CR service; there is a stark contrast in completion between those living in areas in the least deprived quintile and the most deprived. Caution should be taken when reviewing exact figures as there may be reporting errors on the local data and patients may have moved since completing the programme.

Aim

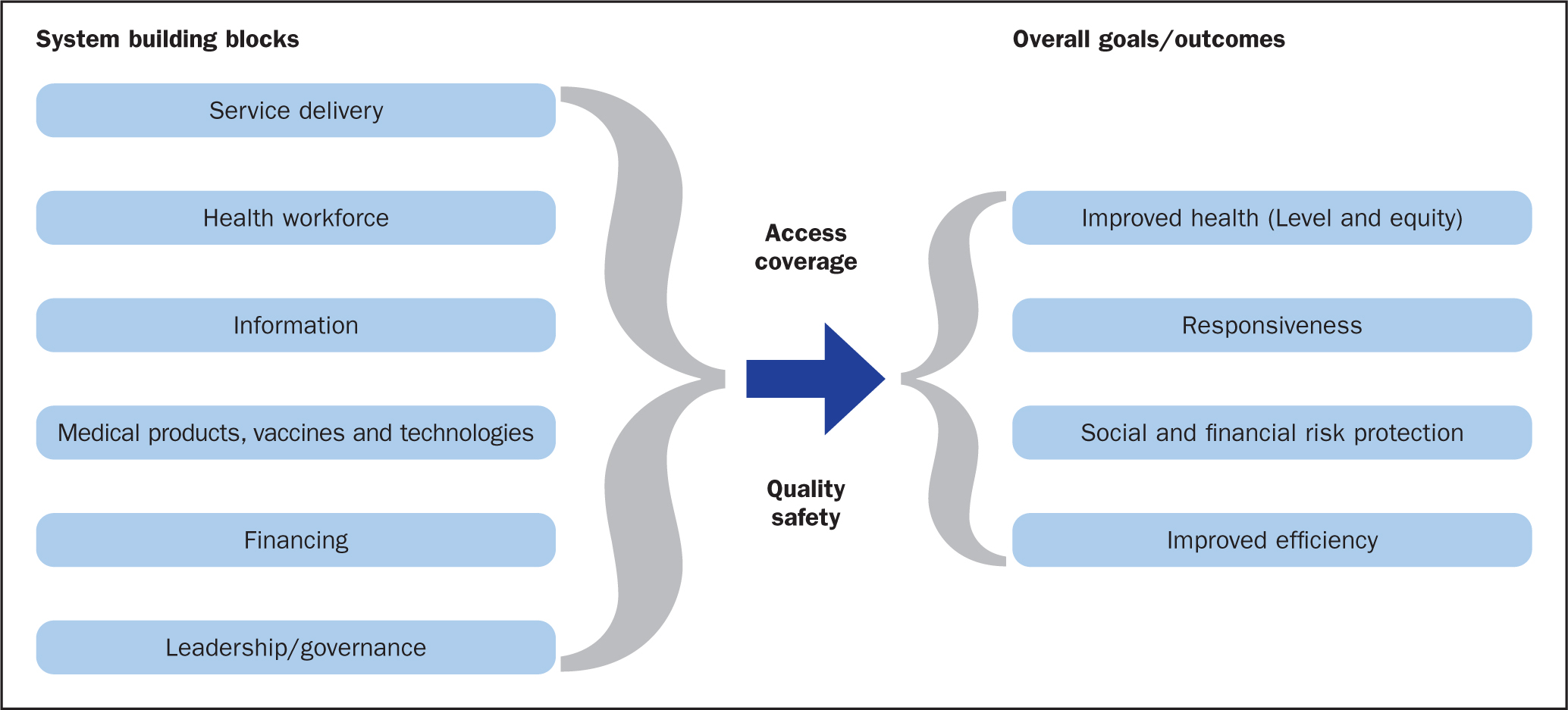

This service evaluation aimed to uncover the barriers and facilitators contributing to the observed patterns of low attendance to CR within Coventry, thereby identifying areas for service improvement. The analysis was structured around the World Health Organization (WHO) (2007) Building Blocks Framework and gave insights into how the Coventry CR service can increase facilitators and reduce barriers to increase completion rates of CR of patients living in areas of high deprivation (IMD quintile 1).

Methods

Existing research on CR completion in high-deprivation areas was quantitative and focused on the numerical differences within deprivation quintiles (Doherty, 2018). Understanding reasons behind these trends required a more in-depth service evaluation. Therefore, one-to-one semi-structured interviews were chosen to obtain participants’ views. An interview guide was designed to probe patients on their likes and dislikes of the programme as well as on the facilitators and barriers that encouraged and prevented individuals from attending. A process map was completed to provide an understanding of the current service and clinical pathway.

Ethical approval

This was a service improvement initiative and not classified as research requiring ethics committee approval, as confirmed by the NHS Health Research Authority online tool (https://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/result7.html). Approval to carry out this service evaluation was obtained from the hospital's research and development department. The service evaluation design addressed a number of ethical issues: mitigating the risk of unanticipated harm and exploitation of patients, protection of participant information, and ensuring patients are adequately informed of the nature of the service evaluation (DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree, 2006). All participant information was confidential, and patients had the freedom to withdraw at any time.

Patient and public involvement

The service evaluation was presented to the University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire Patient and Public Research Advisory Group on 26 May 2022 at the design stage of the project. The questions were tailored in response to this meeting to ensure appropriate, understandable language was used. The group welcomed the project as it aimed to improve health outcomes across the service.

Participant enrolment

Once screened according to the criteria (Table 1), patients were enrolled by a health professional. The health professional on the team purposefully selected participants from the list of eligible patients taking into consideration characteristics such as CR completion/non-completion, language spoken, demographics and sex, to ensure a wide variety of viewpoints and to allow for maximum variation.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Patient information sheets were given in person or delivered via post. Participants had at least one day to review the information sheet before the interview. Non-English language speakers were known to have an English-speaking relative able to translate the participant information sheet. Translators were able to confirm that the participant had read and understood the sheet and consented to take part. All English-speaking participants had a basic level of reading comprehension in line with the consent text. In cases where a patient raised a question or concern, indicating that they did not understand and/or were unable to read the documentation, the consent text would have been read out to them. Written consent was taken prior to the interview if completed face to face, verbal consent was taken if the interview was completed over the telephone. The consent form was read to the participant over the telephone if completed verbally. A question was asked to confirm that the participant had read and understood the consent form. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Data collection and analysis

One-to-one semi-structured interviews were completed after the patient had finished the CR programme, regardless of completion status, between May and August. The participant had the choice of attending the interview face-to-face or via telephone. Interviews were conducted in the patient's language of choice, using live telephone translators. The mix of platforms and use of translators was chosen to improve the reach by reducing language and accessibility barriers. The interviews lasted approximately 10-20 minutes using the interview guide and probing questions. Interviews were stopped once saturation had occurred.

Thematic analysis was used to identify and code themes emerging from the data. Themes were retrospectively confirmed with a second evaluator (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The WHO (2007) Building Blocks Framework was used to analyse the results (Figure 2). Although this is designed to evaluate entire health systems, the building blocks can be used to assess specific health services. The framework was used here because it is a well-known method for analysing systems and services to improve access and coverage to reduce inequity, while also providing a lens to view the results in different contexts.

Results

Coventry Cardiac Rehabilitation Pathway

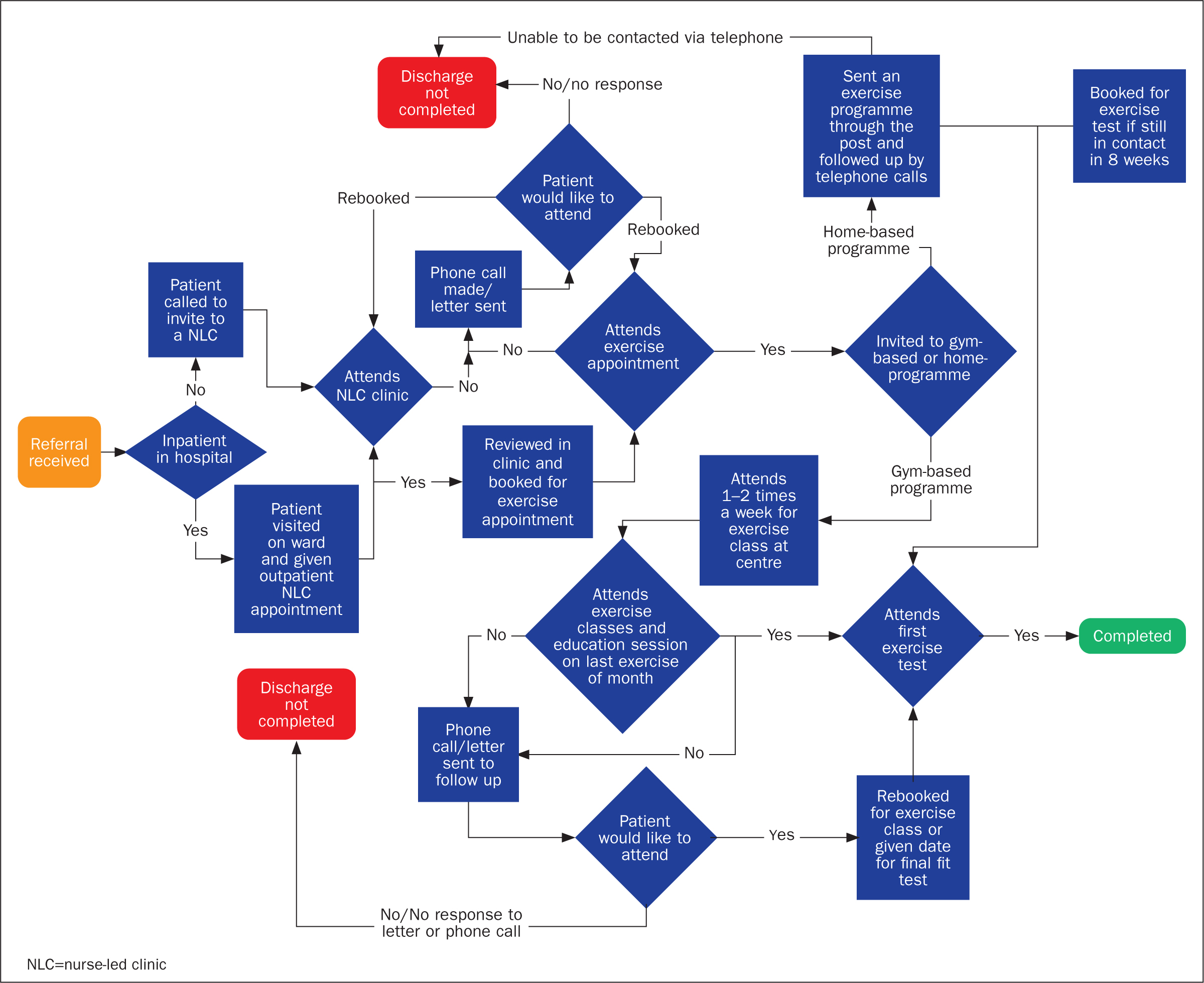

The current CR process is outlined in Figure 3. Patient referral to the CR programme was via two pathways: patients admitted for heart attack (MI) are referred while in hospital, whereas patients presenting with other heart problems, such as following surgery or heart failure, are referred at the completion of care for the health event in question. Patients are booked a clinic appointment with a nurse and an individual exercise appointment. During this appointment they complete an exercise test to create a personalised exercise programme. The patient is then offered a variety of class times to attend the gym-based programme twice a week. Once a month, in place of an exercise class, an education class is delivered on a range of topics, which include risk factors for coronary heart disease, exercise and medications. The gym-based programme is located in Coventry city centre, in a gym specialised for cardiopulmonary rehabilitation (https://www.atrium-health.co.uk/facilities).

If a patient is unable to attend the centre, they will be offered a home-based programme and followed up via the telephone. There appears to be no structured follow-up as patients were not always contactable via the telephone for review. The appointments are not scheduled for the home programme. No structured education session is given via this pathway. All patients on the home-based programme have at least one face-to-face exercise assessment to be able to prescribe the activity.

Completion is defined as documented interaction for 8 weeks and a formal final assessment (BACPR, 2023). The final assessment is a repeat exercise assessment to evaluate the improvements made over the 8 weeks and a discussion to develop a long-term exercise plan. This is an in-person assessment whether the exercise programme has been completed at the gym or at home. Drop-out is defined as patients leaving the programme before completing this final assessment.

Patient characteristics

Twelve patients took part in the service evaluation. Table 2 outlines the patients’ characteristics, including their sex, employment status, diagnosis, language and IMD quintile. There were slightly more male than female patients (7 versus 5). This is similar to CR uptake trends across the UK. Seventy percent of patients answered questions on employment and were employed full or part-time. Two-thirds of patients completed the CR programme. Most patients started on the face-to-face programme.

| Patient characteristics | n=12 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 5 |

| Male | 7 |

| Employment status | |

| Full time | 4 |

| Part time | 3 |

| Self-employed | 0 |

| Unemployed | 2 |

| Not answered | 1 |

| Retired | 2 |

| Qualifying diagnosis | |

| Heart attack | 10 |

| Heart failure | 1 |

| Valve surgery | 1 |

| Language | |

| English speaking | 10 |

| Translator needed | 2 |

| Cardiac rehabilitation completed | |

| Yes | 8 |

| No | 4 |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile breakdown by decile | |

| Decile 1 | 9 |

| Decile 2 | 3 |

| Mode of cardiac rehabilitation started | |

| Face to face | 9 (1*) |

| Home-based | 1 (1*) |

| Hybrid | 1 (1*) |

| Neither | 1 (1*) |

Themes from thematic analysis

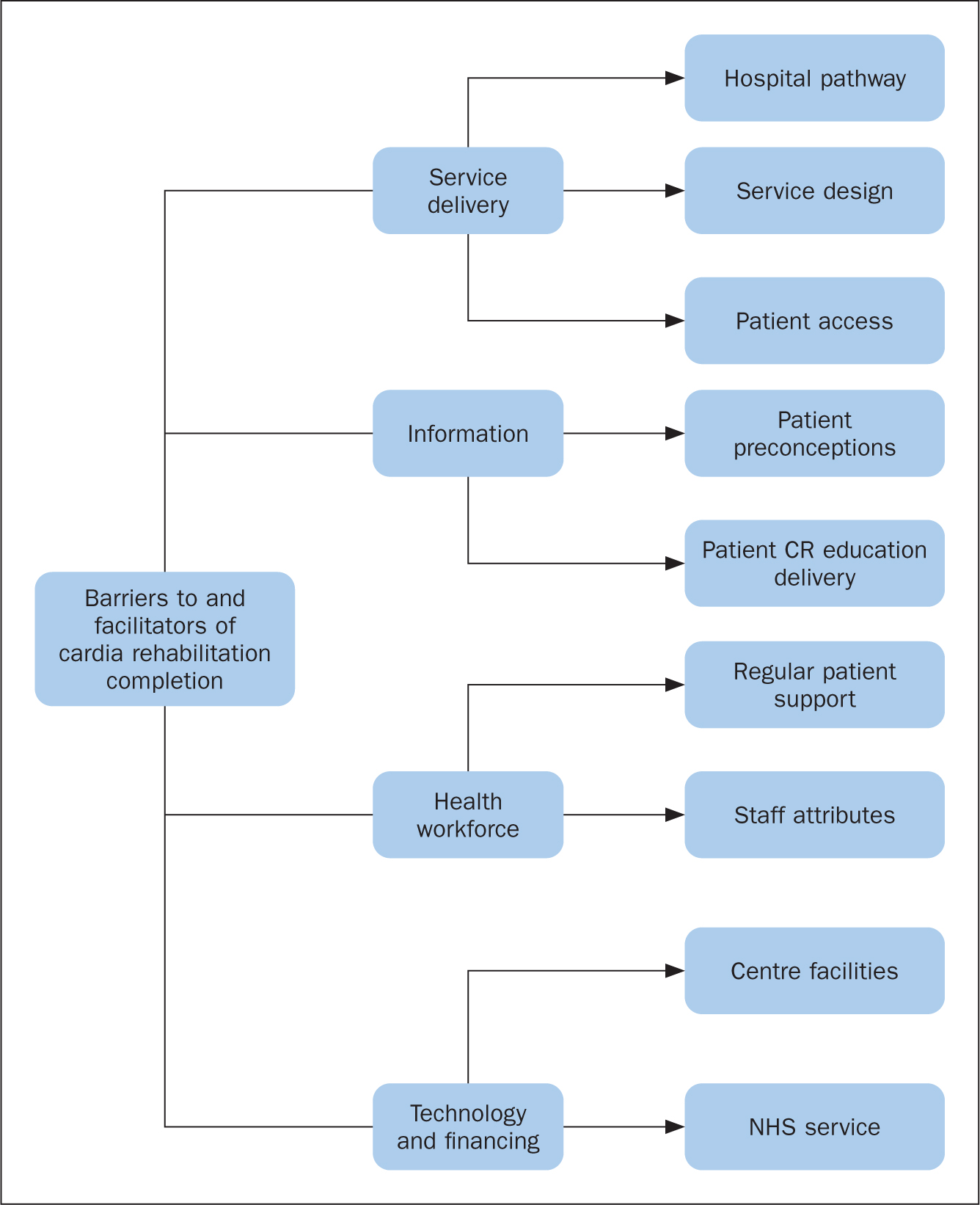

The thematic diagram (Figure 4) illustrates how the themes are interlinked. It identifies the importance of themes, such as service design, patient preconceptions, education delivery and staff attributes, to completion of the CR programme.

The WHO Building Blocks Framework was used to code the interviews, with four building blocks identified as barriers to and facilitators of CR uptake and completion:

Service delivery

The service delivery of CR was a key theme for completion. Patients focused on the delivery of the service itself, the physical environment, and how these played a role in their overall experience.

The design of the CR service itself was both a facilitator and a barrier. Patients described liking the personalised gym-based programme:

‘I also was given some exercises that were suited to my needs.’

‘Good staff downstairs helping me go round and increasing the workload every other week or so.’

No patients on the home-based programme discussed whether their exercise programme was followed up or progressed during their course as with the gym-based programme. Similarly, home-based programmes highlighted structural issues with only some patients having a final in-person assessment booked and others not receiving this final session and being discharged as not completing the CR course.

Preferences for length and timing of the programme varied by patient. Some patients wanted the programme to be longer, whereas others wanted to finish the gym-based programme to finish sooner and continue at home:

‘I was happy that you guys went out your way to design a plan and send it to us. I can do it at home where I feels more comfortable.’

‘I decided to finish at my own will so I can carry on walking on the treadmill in my own house.’

Patients discussed the timings of the classes with differing views. One liked having the routine of a specific time of day to exercise:

‘I mean, I needed to get into that mindset. Previously, I would say, “I can't do it today, I will do it tomorrow”. Put it off. But when you know you're going to go at a certain time, date and days. Whether it is twice a week, Monday and Thursday. You gear yourself up.’

However, other patients did not:

‘I enjoyed coming in on my times and not the specific times that were set.’

Some patients missed weeks of the programme due to family commitments, hot weather and holidays. One patient was discharged due to going on holiday; at the time of the interview, they were keen to re-enrol and finish the programme.

Patients discussed how work flexibility was a key influence on whether they could attend. Some patients who needed to return to work did not complete the programme:

‘Uh, actually, I was at work when I had the heart attack and after seeing that they didn't want it to happen again. So, you know, there was no question of any problem with me having the time off.’

‘The only reason I could not come to the cardiac rehab centre is due to work commitments.’

The gym was a new environment for most patients. Many patients described apprehension ahead of attending, which disappeared the more they attended the centre:

‘The thought of a gym I wouldn't go. Me and gyms don't go. When I actually joined, went to the gym, I was really amazed at how good you all are and you do everything you can for us.’

However, others described struggling to adapt to new environments, which was a reason for not completing. For one patient, adapting was a daunting prospect, and they concluded that gyms were not for everyone:

‘Sometimes you have to realise that there are people out there that – it is all new to some people. And that we're not all the same. Different age groups and… you know.’

Many patients who attended the gym-based programme discussed the importance of the social aspects of not exercising alone and feeling part of a group. Half of the patients reported that they enjoyed being in an environment where they could relate to others, some patients reported building friendships as part of the programme, and others appreciated the opportunity to speak with others about their condition, which motivated them to continue:

‘But I think it's part of being in the group. That made it a bit more interesting rather than just going to the gym on your own and going on exercise machines.’

One patient reported that, if they had known there would be a gym-buddy that they would see every week, they would have completed the programme. One participant could not relate to others in their group so did not want to continue in that environment.

The physical environment was raised by many patients. Patients on the gym-based programme were impressed with the facilities of the gym:

‘All the equipment is there.’

They said that it looked clean and tidy and had all the equipment necessary. General facilities were also an important factor in attendance. Those attending in the heatwaves of June/July/August 2022 reported difficulty attending, both due to transport and the facilities being unsuitable.

‘Air conditioning! In this room it's nice and cool, but downstairs in the gym it can be really hot. I came in one day and was told to go home as it was too hot.’

One-third of patients discussed the location of the centre, as a factor in attendance. This was often linked to being able to get there:

‘Parking! It's a funny area for parking.’

Patients liked being able to park directly outside the centre or preferred to be able to walk. Patients also discussed attending by taxi or via bus, noting varying degrees of difficulty or ease.

Information

Another main factor for CR completion was the communication of information and delivery of patient education. Patients had varying levels of understanding about what the programme entailed. Patients attended based on advice given by medical staff, or on their discharge summary, and thought that this was the typical process after having a heart attack. One reported:

‘It wasn't a case of wanting to come, you know … it's just part of the problem from that attack.’

One patient said that they had attended because:

‘There is no cardiology follow-up to check how I am. That's why I came to rehab you see.’

Patients used family to help support understanding with translation and explanation of the exercises.

Many patients felt that the gym programme was thoroughly explained, with education sessions adding to their understanding of the programme. However, some did not think that it had been made clear what the programme entailed at their initial appointment, which led to drop-out. Patients on the home-based programme did not seem to receive the same support, reporting that they lacked understanding of their exercises:

‘There was an initial difficulty as he was struggling to understand what the [home] exercises were about.’

The education sessions for the gym-based programmes were seen as a positive. Patients reported that these added understanding of why they were attending. They also created motivation and awareness of risk factors and how to manage them.

‘The education side of it has been brilliant. Really educational. I liked the gym side of it, but really liked the classroom side of it. Education, dietitian – that type of thing,’

‘Also what I liked is the that you give us an understanding of what is a heart attack. What is this, what is that. Talks or seminars. Whatever you want to call them. It's good. I enjoy it. It makes you realise why you are doing things, you're not just doing it for the sake of doing it. General understanding.’

Those on the home-based programme or who did not attend education sessions had less awareness of how to reduce cardiovascular risk:

‘No … Nooo. I take my medication and that's it, isn't it? There is nothing more I can do after that. You know?’

This also applied to patients who did not complete the programme, which showed that they had less knowledge of the risk factors.

Patients also set goals and had personal motivations for completing, such as improving their health and risk factors, and the desire to return to normal. Patients found the motivation to continue with the programme by seeing improvements in their health, both at the final exercise test and during the programme, with staff feedback and programme increments:

‘Don't remember completely, but I think it was 40-something when I first went. Uh, and it's 75 or something like that when I finished. OK, yeah. So yeah, it's quite the jump up.’

Health workforce

Staff were responsive, friendly and positive; many patients on the gym programme completed it because they knew the staff would support them if they were unwell. The staff were also there to adjust the programme if it caused any problems or to provide assistance when a patient was struggling:

‘They helped when my heart rate was very low. [muffled] I couldn't walk. I couldn't do anything.’

Patients commented that they had continued to attend the gym-based programme because staff regularly walked round and offered advice and support while they were exercising:

‘They are always watching. They come and talk to you. They talk to everybody. And it is very good.’

Several patients discussed the safe environment and monitoring as a facilitator to continue attending:

‘Happy to come here and have medical supervision, sort of thing.’

There were no comments regarding follow-up for those on the home-exercise programme.

Technologies and financing

Technology was an important facilitator and was used for contacting patients and monitoring them in the gym. Patients for the home programme were contacted for appointments via the telephone and received printed exercises by post. One patient reported confusion around this: he had to consult family but ‘got the jist’ of what he needed to be doing (Participant 112). Telephone and a printed exercise programme is the only technology used in this mode. There is no heart rate monitor, unlike with the gym-based programme.

Regarding the gym-based programme, one a patient reported:

‘They monitor you … It gives you meaning why you are doing it.’

Patients in the gym-based programme are given heart rate monitors and exercise equipment prescribed at certain intensities. These patients were impressed with the facilities of the gym. They discussed how it looked clean and tidy, and had all the equipment necessary:

‘All the equipment is there.’

One patient mentioned that CR ‘is part of the NHS’ (Participant 109), and wanted to use the resources being offered. This means, unlike in many other countries, that the cost of the CR service is not a barrier. However, secondary costs such as missing work and getting to the centre should be considered – although these were not explicitly mentioned by any patients.

Discussion

The evaluation showed that there are two main ways the Coventry CR programme can increase facilitators to completion: by increasing the programme's flexibility to suit patient needs, and by improving patient education during the programme.

One barrier included the need to return to work. For those whose workplace was flexible, who were not working or retired, the gym-based programme offered a personalised regimen and involved programme facilitators such as friendly staff responding to needs, offering a safe environment with regular ‘check-ins’ and exercise changes. This is supported by BACPR guidance, which dictates that patients should have a personalised programme with regular reviews and exercise progression: the importance of personalised exercises in CR programmes is well known (BACPR, 2023; Squires et al, 2018; Mytinger et al, 2020). Those participating the home-based programme were less likely to have the same level of personalisation or review, which is an area that warrants scrutiny.

Although the exercise prescribed to patients is personalised, the service delivery also needs to be adapted to the individual patient. The evaluation illustrated that the programme needs to be more flexible in its approach, adapting around patient commitments. Patients are given a choice of specific appointment class times (11:00, 12:00, 13:00 or 14:15) during the week. These do not accommodate those who have returned to work. The importance of service flexibility is also reflected in the wider literature, with studies showing the advantages of telemedicine such as video appointments, mobile apps and wearable devices (Knudsen et al, 2021; Hoff et al, 2022). The use of technology is likely to increase completion as the programme reflects patients’ self-image, prior lifestyles, and schedules (Knudsen et al, 2021; Hoff et al, 2022).

The use of telemedicine provides patients with feedback, monitoring and medical supervision, which was a main motivator for completion of the gym-based programme, and would support staff with exercise progression for a home programme. The COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing restrictions meant that nationally there was an increase in home programmes, but only 20% were validated and patients had minimal to no communication from CR staff (Doherty et al, 2021). Currently, the only technology used alongside the home programme is the telephone, used to undertake consultations, which are unstructured and only allow verbal interaction. Alternative technologies and methods of communication should be sought to aid communication, such as text messaging and video conferencing at different times, as appropriate (Thomas et al, 2021). Further research would need to be completed into the acceptability and logistics of facilitating telemedicine in this target group. Technology-assisted CR has been shown to produce comparable results to gym-based programmes (Chong et al, 2021).

Other facilitators included patient education delivery as a key component of CR, helping to motivate participants to exercise and to reassure those with preconceptions, and raising awareness of cardiovascular risk factors. The delivery of patient education sessions on exercise, risk factors and medication during the centre-based programme created an understanding of why they were attending, motivating patients to continue.

Information is also needed to outline what CR involves, as many patients are unaware of what the programme is and what to expect. Further information on what the process entails may help to decrease anxiety. Preconceptions of the gym environment and the ‘not for me’ phenomenon are well known; studies suggest the importance of good explanations and education to overcome these misunderstandings (Herber et al, 2017).

Nationally, existing education resources for home-based CR programme are books such as The Heart Manual (NHS Lothian, 2014) and the REACH Heart Failure Manual (NHS Lothian, 2025). However, these materials are targeted at literate, English-speaking adults and are unavailable in other languages. These texts do not meet the needs of the Coventry population: 10% do not have any educational qualifications and 3.8% have limited to no English language (Coventry Health and Wellbeing Board, 2019; McLennan et al, 2019; Varbes, 2024). The REACH-HF study also focused on uptake rather than completion, and no information could be found on the education levels needed to understand the material (Dalal et al, 2019). Further resources need to be produced to support individuals on the home programme to learn the importance of cardiovascular risk factor management to improve services, both in Coventry and more broadly within areas of high deprivation. The replication of gym-based education programmes at home would require a review of the telemedicine provision, to ensure personalised education materials were suited to the needs of the population.

The wider literature indicates the importance of ensuring that physical activity is something that patients enjoy; this is a common motivator for completing, reported both in the literature (Angel, 2018) and in the evaluation. Although some patients thought that they would not enjoy the gym environment and later did, the gym was not for everyone. Hybrid programmes would increase flexibility, focusing on increasing exercise uptake. Studies in the USA found that hybrid programmes can be offered as an alternative, to overcome geographical and work barriers, with repeated staff contact and engagement of family and friends as solutions to overcome barriers of the hybrid method (Keteyian et al, 2022). This resonates with data from the evaluation, highlighting the importance of family engagement and accessibility.

In the UK, the financing of attending CR is not a barrier due to the provision of the NHS; this is unlike similar studies around the world, which list lack of health insurance as a barrier (Bennett et al, 2019). However, no patients discussed their financial situation, including the costs of attending the centre or attending CR instead of working. This is likely to be a factor, because 33% of Coventry households with children are regarded as low-income families (Coventry Health and Wellbeing Board, 2019). The rising cost of living means that further work should be completed to provide CR home services to the same standard as the gym-based equivalent to cater for all financial needs (Handscomb et al, 2022; Francis-Devine et al, 2024). The financing of the CR service itself is outside the scope of this project, but future work should be undertaken on whether the service is financed appropriately to achieve its objectives.

Strengths and limitations

To the authors’ knowledge this is the first service evaluation using a qualitative methodology to investigate non-completion of CR in patients living in high-deprivation areas. Thematic analysis provides valuable descriptions of data, while identifying unexpected insights into phenomena (Nowell et al, 2017). Therefore, as deprivation within CR is a sparsely researched topic, this can start to highlight new understandings of the barriers to and facilitators of completion of CR programmes.

As the primary evaluator was a CR nurse, there may have been social desirability bias in some of the patients’ answers preventing them from being fully open about their experiences. To try to overcome this, all patients approached had finished the course and had been discharged from the service. Research bias was reduced as the themes were retrospectively confirmed with another evaluator.

Purposive recruitment efficiently captures the views of seldom heard populations (Barratt et al, 2015). Individuals living in high-deprivation areas are a seldom-heard community, due to low attendance at clinic appointments (Ellis et al, 2017). It is recognised that this sampling method reduces rigour and means that the study is ungeneralisable (Barratt et al, 2015). That said, generalisability is beyond the scope of this study because its focus was service improvement of Coventry CR services. Sample size was dependent on data saturation; this added rigour to the study and is the gold-standard technique in purposive sampling for identifying sample size (Saunders et al, 2018).

Inability to contact patients who had returned to work or were uncontactable via the telephone may have caused a responder bias. It must be noted that none of the patients were self-employed, so they may have already returned to work due to their financial situation and further research needs to be completed in this area.

In line with guidance on use of the WHO framework, it has been adapted to be context specific; ‘governance’ was outside the scope of this project (Mounier-Jack et al, 2014). Further work should be completed to evaluate whether the BACPR objectives such as CR duration of 8 weeks remain in line with current research on successful behaviour change (BACPR, 2023). Person-related factors of non-attendance at CR may also have not been captured in this framework, therefore further research could be completed in this area.

Future service evaluation

CR is a vital service to help reduce health inequalities and improve population health. Other CR services across the country should complete evaluations of their own service to ensure that the programmes we are providing suit individual population needs. After completing the service evaluation, Coventry CR is in the process of enhancing their current home exercise programmes with consideration of the factors discussed, with a more formal structure, clearer communication and use of technology to enhance the offering. It should allow for staff to be able to provide motivational support, education, monitoring, and feedback, alongside regular progression, ensuring that it maintains quality, safety and positive outcomes. An impact assessment should be completed post implementation to evaluate the new programme.

Conclusion

Although CR has proven benefits and is successfully completed by many patients, more needs to be done to increase its accessibility and prevent it widening the health inequality gap. This service evaluation illustrates that a combination of factors can increase completion within Coventry. The gym-based programme is personalised with feedback and progression. Patients enjoy it, particularly the education, social aspects, facilities and interactions with staff. The framework illustrates that there is a strong health workforce successfully delivering a gym-based programme, but the use of more technology is needed to advance the home-based programme. This will enhance communication with patients for education purposes and allow for feedback, so that exercise progression can take place and increase accessibility to those who are unable to attend the centre for 8 weeks. Patients living in areas of high deprivation have barriers such as work, family commitments, transport, and gym pre-conceptions often making it harder to attend the centre. The service delivery needs to be improved to allow patients to receive the same care at home as they do at the centre.