On a general adolescent inpatient unit for young people with mental health difficulties (including anorexia nervosa and affective, anxiety and psychotic disorders), staff and patients identified room for improvement in physical healthcare provision. Until this point, physical health reviews and investigations were done on an ad hoc basis.

The Trust's physical health policy and relevant national guidance lists a wide range of factors to be covered, including lifestyle risk factors, pre-existing health conditions, screening, medication management and health promotion (Shiers et al, 2014; NHS England, 2014; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2015; Department of Health (DH) and Public Health England (PHE), 2015; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2016; DH and PHE, 2016; NICE, 2017). It was difficult to keep track of each person's care. Feedback from the patients indicated they wanted a planned approach to appointments and access to information on healthy living topics.

Aim

The aim of the project was to establish a wellbeing clinic to improve:

Background

Individuals with severe mental illness have an increased risk of physical health problems and an associated reduced life expectancy of between 13 and 30 years (De Hert et al, 2011).

The Lancet Psychiatry Commission recently stated:

‘Protecting the physical health of people with mental illness should be considered an international priority for reducing the personal, social and economic burden of mental health conditions.’

Physical health problems most strongly associated with mental illness are stroke, myocardial infarction, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, obesity and HIV. There is evidence that hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis, osteoporosis, poor dental status, impaired lung function, sexual dysfunction and diabetes mellitus are similarly associated. This physical health disparity arises early in life (Firth et al, 2019).

The reason for the early appearance of poor physical health is likely to be multifactorial. First, people with mental illness are less likely to access routine preventive services or receive treatment for physical health issues. For example, they are less likely to receive care for hyperlipidaemia or have access to oral health care (Hippisley-Cox et al, 2007; Kisely et al, 2015).

Second, smoking, excess alcohol use, sedentary behaviour, poor sleep and poor diet are all more common in young people with mental health difficulties and may precede illness onset (Carney et al, 2016; Firth et al 2019).

Third, anorexia nervosa disproportionately affects younger people. These individuals are at risk of refeeding syndrome in the initial stages of treatment, alongside longer-term effects of low weight and malnutrition, such as osteoporosis. They have the highest rate of premature mortality of any mental disorder (Arcelus et al, 2011).

Fourth, medications such as antipsychotics are associated with weight gain, metabolic dysfunction and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Correll et al, 2017). Finally, individuals with severe mental illness are more likely to be admitted to an inpatient ward. This admission is often crucial in delivering high-quality mental health treatment but also exposes the patient to an environment that has been described as ‘obesogenic’ (Faulkner et al, 2009). Several factors may contribute to weight gain, including less access to physical activity or nutritious food (Faulkner et al, 2009; Every-Palmer et al, 2018).

Young people admitted to an inpatient mental health unit are therefore at high risk of poor physical health. This is supported by a study showing that approximately half of adolescents admitted had one or more physical or metabolic abnormalities (Eapen et al, 2012).

Inpatient admission offers a unique opportunity to assess young people and engage them in their physical wellbeing at a formative stage with the potential to confer lifelong benefits (Bailey et al, 2012). Despite this, there is surprisingly little evidence for the use of interventions to improve physical health in adolescent inpatients. One such report exists appraising the use of a checklist to prompt antipsychotic medication monitoring (Pasha et al, 2015). The recent Lancet Psychiatry Commission report recommended simultaneously considering multiple lifestyle factors, alongside using biological markers, to aid early intervention, but noted the lack of suitable tools available to assist with this (Firth et al, 2019).

Methods

The plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycle was used by the authors to drive this quality improvement project, using audit and re-audit as the ‘study’ element.

This article is structured to reflect this methodology, discussing baseline measurements, design and strategy.

Baseline measurements

A pre-intervention audit investigated whether patients were receiving appropriate physical health input during their admission. Specific audit criteria were devised, linked to the aims of the project:

For the baseline, 12 patients admitted in 2015 were retrospectively selected alphabetically. This mirrored the number of inpatient beds and provided data across the year. The only exclusion criterion was an admission for less than 1 week as this may not have allowed all measurements to have been collected.

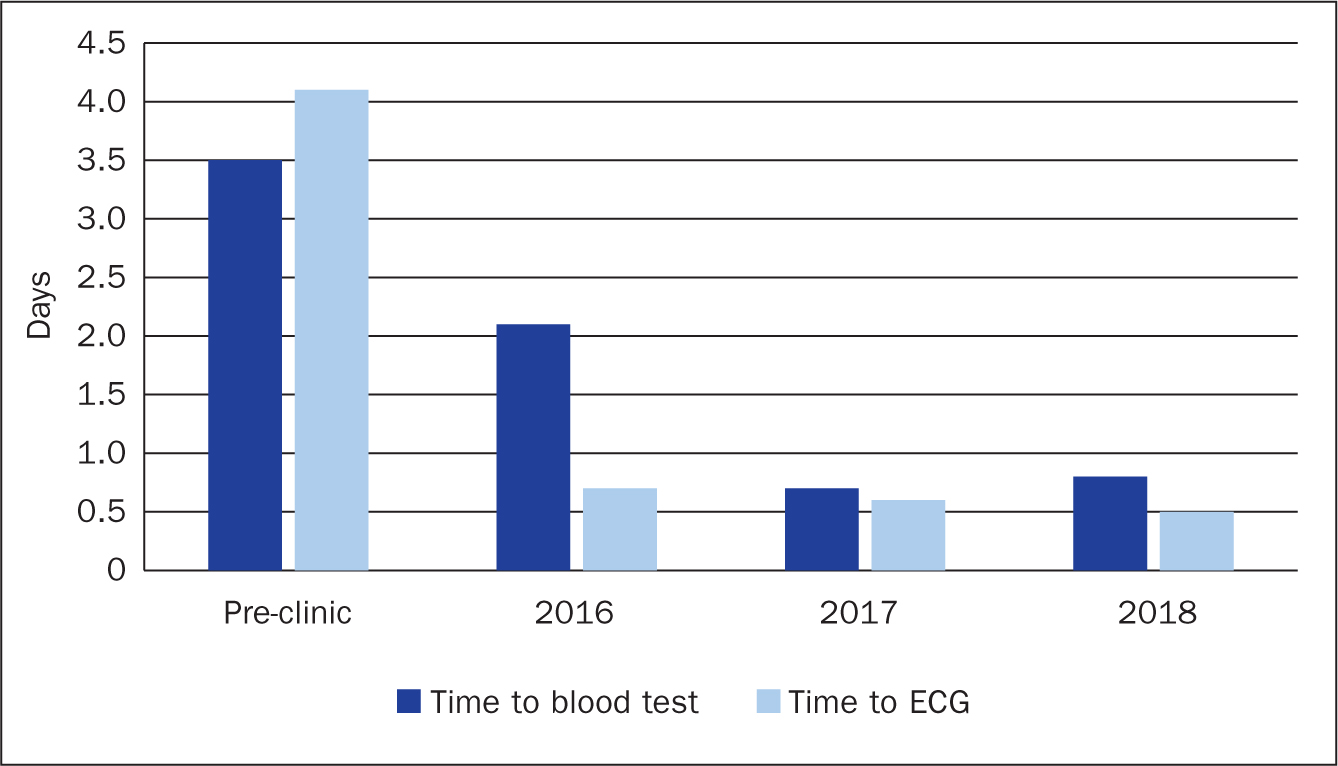

The results revealed several areas for improvement. In summary, although all patients (aside from one who refused) had blood tests, these were taking a mean of 3.5 days to complete (range 0-17 days). The local Trust policy stated that an ECG should occur within 72 hours of admission; 5 out of 12 patients had not had an ECG and, for those who did, it took a mean of 4.1 days. Only 9% of patients had evidence of a body map being completed.

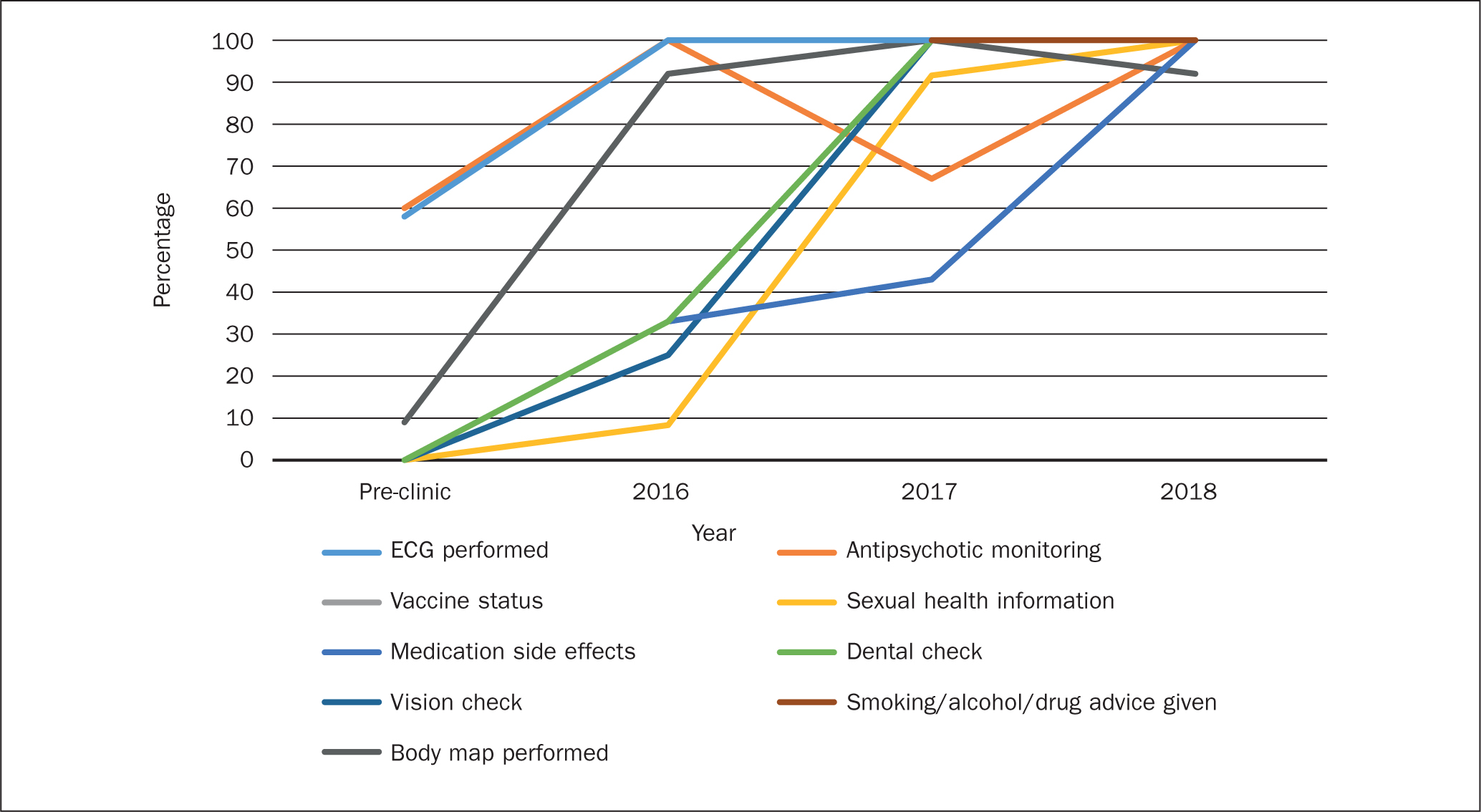

Four patients were taking antipsychotic medication; correct monitoring (Shiers et al, 2014) was recorded at only 60% of time points. There was no documented evidence of discussion about side effects, vaccines, or sexual health or that information about cessation of smoking, drug use and excess alcohol use had been given.

Design

The authors felt that the challenges faced on the ward required them to dedicate allocated time and staff for physical health. It was decided that the ward needed a weekly half-day ‘clinic’. The clinic was designed to see all patients in their first week of admission and thereafter every 4 weeks. Admission and review questionnaires were developed based on the requirements laid out in the guidelines mentioned previously to improve staff compliance with them all. They guided the clinic staff to check admission physical health tasks are completed, to ask about current health, medication and medical history and to offer healthy living information.

The clinic was managed by a staff nurse (with paediatric nurse training offering a valuable perspective) and two support workers, whose shifts were arranged to cover the service. The nurses worked closely with the ward doctors to address issues that cropped up, and with the school unit to minimise disruption. There were four or five5 booked morning sessions each Wednesday (for newly admitted patients, those who had asked to be seen and those who needed a blood test or other investigation) and a drop-in session over lunchtime.

A tablet device was obtained so that clinic notes could be documented on the patient record contemporaneously. Patients could bring issues that had arisen for them that week and information leaflets on healthy living topics, medications and side effects could be supplied. If preferred, patients could be supported to research information online on the clinic tablet device. Patients took away information to store in the ‘physical health’ section of their inpatient unit folders.

Strategy

PDSA cycle 1

PDSA cycle 2

PDSA cycle 3

Results

The information presented is anonymised and relates to the authors' own clinical practice. There were four data-collection points: baseline measurements in 2015 (12 patients from 2015), 6 months after clinic implementation at the end of 2016, 12 months following this at the end of 2017 and 12 months after this at the end of 2018. At the three post-clinic dates, the records of the 12 preceding admissions were audited. Table 1 summarises the data collected.

| Mean time to bloods (days) | Mean time to ECG (days) | Appropriate anti-psychotic monitoring at 1 month | Appropriate anti-psychotic monitoring at 3 months | Documented information on | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccines | Sexual health | Medication side effects | Dental health | Vision | Advice about smoking, alcohol and drug use | Body map | |||||

| Pre-clinic (2015) | 3.5 | 4.1 (5/12 had no ECG) | 75% (n=4) | 0% (n=1) | 0% | 0% | 0% | Not recorded [0%] | Not recorded [0%] | 0% | 9.% |

| Post-clinic (2016) | 2.1 (P=0.312)* | 0.7 (P=0.448)* | 100% (n=4) | 100% (n=1) | 33% (P=0.093)* | 8% (P=1.000)* | 33% (P=0.093)* | 33% (P=0.093)* | 25% (P=0.217)* | Not recorded | 92% (P<0.0001)^ |

| Post-clinic (2017) | 0.7 (P=0.062)* | 0.6 (P=0.401)* | 67% (n=6) | n/a | 100% (P<0.0001)^ | 92% (P<0.0001]^ | 43% (P<0.0001)^ | 100% (P<0.0001)^ | 100% (P<0.0001)^ | 100% | 100% (P<0.0001)^ |

| Post-clinic (2018) | 0.8 (P=0.093)* | 0.5 (P=0.329)* | 100% (n=6) | 100% (n=1) | 100% (P<0.0001)^ | 100% (P<0.0001)^ | 100% (P<0.0001)^ | 100% (P<0.0001)^ | 100% (P<0.0001)^ | 100% | 92% (P<0.0001)^ |

The null hypothesis: no difference in outcome before or after the physical health clinic

Each different set of results was compared with the initial baseline results. Mann-Whitney U test used to compare two possibly non-normally distributed (non-parametric) group sets of data. One-tailed hypothesis used

non-significant change.

significant change.

The rate of people seen in the clinic during their admission improved from 92% at 6 months to 100% in 2017 and 2018 (by 2018 every young person was seen within the first week of admission). There was a reduction in mean time from admission to blood tests from 3.5 days before the clinic to 0.8 days by 2018 and a reduction in average time to ECG from 4.1 days to 0.5 days (Figure 1).

The proportion of patients receiving an ECG increased from 58% to 100% after clinic introduction and has remained at this level (Figure 2). The number of patients who had a body map documented rose from 9% to 100% by 2017. One record audited in 2018 did not have this documented. Rates of documentation of providing information on side-effects, vaccines, sexual health, dental health and vision improved from 0% (at baseline) to 43–100% by 2017 and 100% across the board by 2018. Full compliance with antipsychotic monitoring had reached 100% at 6 months, dropped to 67% by 2017 and rose to 100% again by 2018.

Before the clinic was established, there was no documented evidence that the people who had declared they smoked, drank alcohol harmfully or took illicit substances were given information about cessation or harm minimisation. The team looked again at this issue in 2017 and 2018. At both time points 100% of people were offered information.

In summary, there has been a significant and sustained improvement in waiting times for physical investigations and blood tests, together with improved documentation of the physical health status of patients and in the regular provision of appropriate advice. Box 2 summarises the perceived benefits of this initiative from the perspective of the team and patients.

Lessons and limitations

The authors believe these improvements were obtained through multidisciplinary team involvement before and throughout the development of the clinic, as well as a clear documentation process, regular audit of the clinic practice and offering regular training to ward staff. This widened their role, increased job satisfaction and ensured that there is continuity and sustainability in the clinic even in the case of staff turnover.

Some objective improvements were noted (time taken to initial investigations and presence of antipsychotic monitoring testing). However, part of what was being audited was based on evidence of documentation. Although the authors assume that better recording and awareness will improve patient care, these measurements do not directly equate to improved patient outcomes.

This evaluation was of a small number of patients in one setting type. There was a difference in sampling between the pre-clinic records (alphabetically across the year) and post-clinic records (preceding admissions). If doing the project again, the team would use the same sampling method for baseline. It is possible that some of the improvements seen could have been associated with something other than the wellbeing clinic intervention, such as raised awareness of guidelines among the staff involved.

Conclusions

Too often the physical health needs of patients with a mental disorder are not fully met, impacting on quality of life and mortality (De Hert et al, 2011). Young people on general adolescent wards in mental health inpatient settings share multiple risk factors for ill physical health (Eapen et al, 2012; Carney et al, 2016), but there is a paucity of evidence regarding interventions to tackle this situation.

Establishing a regular physical health clinic on a general adolescent unit has proved to be feasible and has achieved the aims of the project, and in so doing, the standards set out in the multiple relevant guidelines. The results show improved efficiency, compliance with physical health care and health promotion standards, and medication monitoring.

The clinic has enabled the authors to feel confident that they are managing complex physical health needs in a holistic manner consistent with recent international recommendations (Firth et al, 2019). These findings may be particularly relevant to others working in the mental health inpatient setting, although the principles are generalisable.

The authors recommend that clinicians familiarise themselves with the relevant physical health and health promotion standards and audit their performance compared to these. If there is evidence that areas of physical health care are being compromised, an appropriate intervention should be developed and the impact re-audited. If limited to one area of practice, a simple checklist may be sufficient (Pasha et al, 2015). However, an intervention that covers a wider range of outcomes, as described here, could be necessary to meet more complex needs.

In the future the team would like to build on this improvement in monitoring, screening, health promotion and psychoeducation by continuing to implement evidence-based interventions to improve healthy activity levels, nutrition and sleep and to explore the benefits of nature-based care.