Vascular access is the most common invasive procedure performed on hospitalised patients, but it is not without complications (Loveday et al, 2014). Many of the complications, such as phlebitis, localised infection, bloodstream infection, thrombus, infiltration and extravasation, are preventable (Loveday et al, 2014).

Elderly patients, in particular, often have fragile veins, making cannulation difficult and often involving failed attempts and delayed treatment (Oliver, 2015). Cannulation in the general adult population can also pose challenges, with a reported first attempt cannulation failure rate of 19% (van Loon et al, 2019). The peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC) failure rate before the completion of the intended treatment is reported at around 50%, resulting in further cannulation attempts (Helm et al, 2015). Not only is this unpleasant for the patient but it also involves valuable nursing and/or medical time, wasting both time and resources. The default vascular access device (VAD) for most patients is the PIVC, inserted with little assessment of the vein quality, medicines to be administered or the likely duration of treatment (Jackson et al, 2013).

‘Vessel health and preservation’ (VHP) is an evidence-based concept of VAD management that was originally introduced in the USA (Moureau et al, 2012). The VHP concept is based on proactive VAD selection to achieve minimal damage to the patient’s veins and daily evaluation of the necessity of the device, with early detection of complications. The UKVHP Framework was adapted and developed from the US model to provide guidance on vessel assessment and decision making based on individual need and risk assessment to aid selection of the right device (Hallam et al, 2016). The UK VHP framework consists of four clear sections to aid assessment and decision-making:

- A vein assessment tool, providing a scale of 1 to 5 on the quality of peripheral veins

- A medication suitability section for the safety of the medicines to be given, with consideration of central vein administration

- A right line decision tool for device choice based on vein quality, drug choice and duration of treatment

- An evaluation section for daily assessment of the vascular access device to observe any complications.

The original UKVHP Framework was updated by a working group with members from the Infection Prevention Society (IPS), the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), the National Infusion and Vascular Access Society (NIVAS) and the Medusa Advisory Board in 2020 to ensure that it continues to provide the evidence base for best practice (Hallam et al, 2021). An evaluation of the original UK VHP Framework found that many respondents were aware of the framework and were using it in a range of different ways and found it most beneficial when making decisions on device choice and peripheral vein assessment (Burnett et al, 2018). Following the launch of the VHP2020 it was important to carry out another survey to understand whether the updated framework had reached its intended audience, if it was being used and, if so, how, and the benefits and drawbacks of its use in practice.

Method

A 14-question survey was created and managed on Qualtrics and distributed through anonymous links, which meant that respondents could not be identified. Members of the IPS and NIVAS were invited to participate via email, the IPS President’s weekly digest and via social media posts. Participation was voluntary and consent was implied through completion of the survey. Although none of the questions required personal identifiers, to maintain confidentiality any personal information was de-identified. The survey ran from the beginning of May to mid-June 2022 (approximately 7 weeks). Quantitative data were managed in Microsoft Excel, and a descriptive analysis was performed to explore and understand the responses. Qualitative data provided in free-text responses were organised by frequency to reflect how commonly reported a response was.

Results

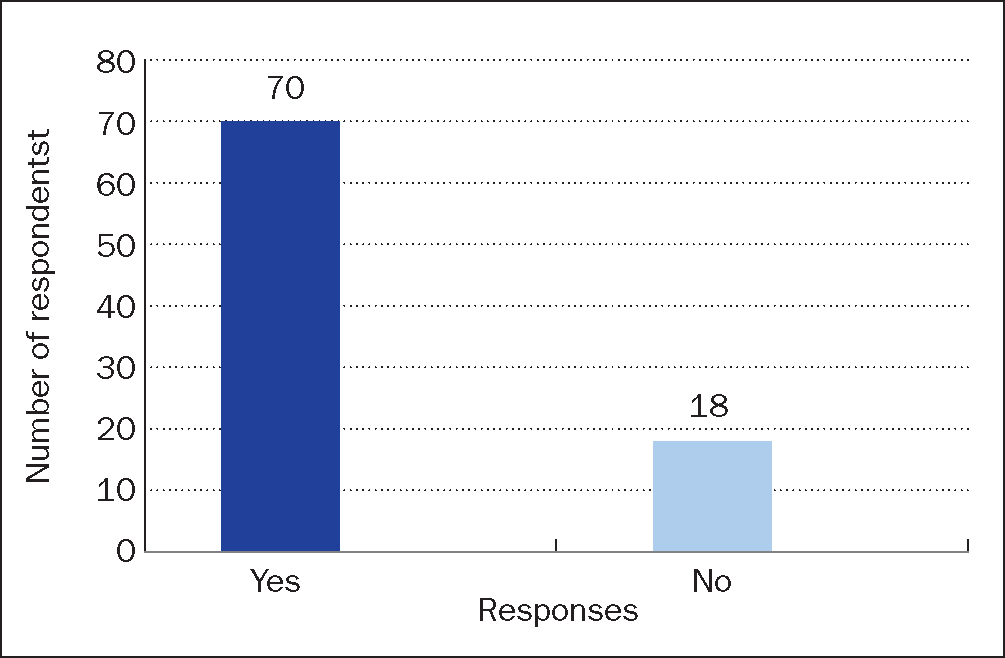

A total of 88 responses were received, 81% (n=71) of responses came from those working in England, a further 7% (n=6) were from the rest of the UK. The other 12% of respondents (n =11) were from outside the UK. Countries cited were Ireland, Italy, Pakistan and the USA and the crown dependency of Jersey. Of the 88 respondents who completed the survey, 80% (n=70) had heard of the VHP and 20% (n=18) had not (Figure 1). Those who had not heard of the VHP were not asked any further questions and were thanked for their participation.

Just under 50% of those who responded to the survey held the role of vascular access specialist (49%, n=43/88), this was followed by the role of infection prevention and control practitioner (16%, n =14) and clinical educator (9%, n=8). Around a quarter (24%, n=21), of those responding to the survey selected ‘other’, citing the following roles: ‘consultant neonatologist’, ‘clinical nurse specialist’, ‘college professor’, ‘critical care outreach’, ‘lead advanced clinical practitioner’, ‘lead cancer nurse’, ‘lead nurse’,‘nurse’, ‘oncology clinical nurse specialist’, ‘OPAT (outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy) nurse’, ‘Pharmacist’, ‘PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) practitioner’, ‘renal dialysis’, ‘RGN ITU (intensive therapy unit)’, ‘field nurse manager’,‘charge nurse’,‘critical care outreach’, ‘CVAD (central venous access device)/PICC nurse’, ‘nursing researcher’, ‘recovery nurse’. Two respondents did not specify their role and two respondents stated the same role.

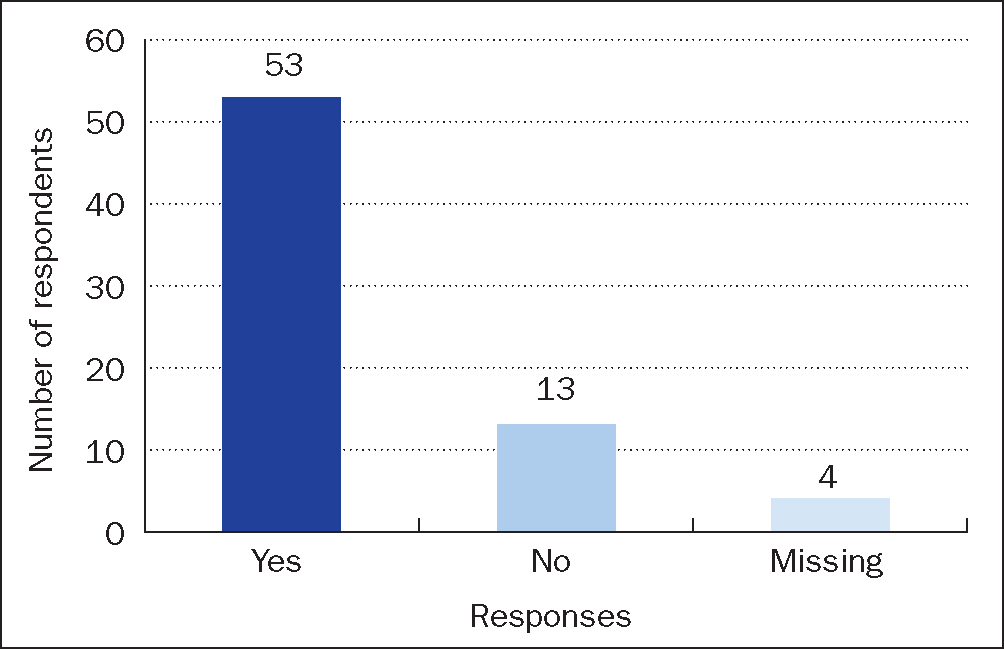

The remaining 70 respondents who were aware of the VHP were asked if they had heard of the updatedVHP2020. Fifty-three (76%) had heard of it (see Figure 2). Thirteen (19%) respondents were not aware oftheVHP2020.These respondents were asked no further questions and thanked for their participation. Four respondents (6%) stated that they had heard of the updated VHP2020 but did not complete the survey any further.

Five respondents were using the original VHP with four out of the five having heard of the updatedVHP2020 Framework. Two provided reasons for not using the updated framework, these were:

‘We haven’t got around to study the updated version to understand the changes as yet.’

‘… it’s something we are working on.’

The majority of respondents who had heard of the VHP2020 (n=53) reported learning about the update via the NIVAS email (32%, n =17/53), followed by learning about it from a work colleague (21%, n=11/53). Other respondents cited ‘literature search’, ‘third-party publishing and the internet’, and ‘the help text from Medusa Monograph’.

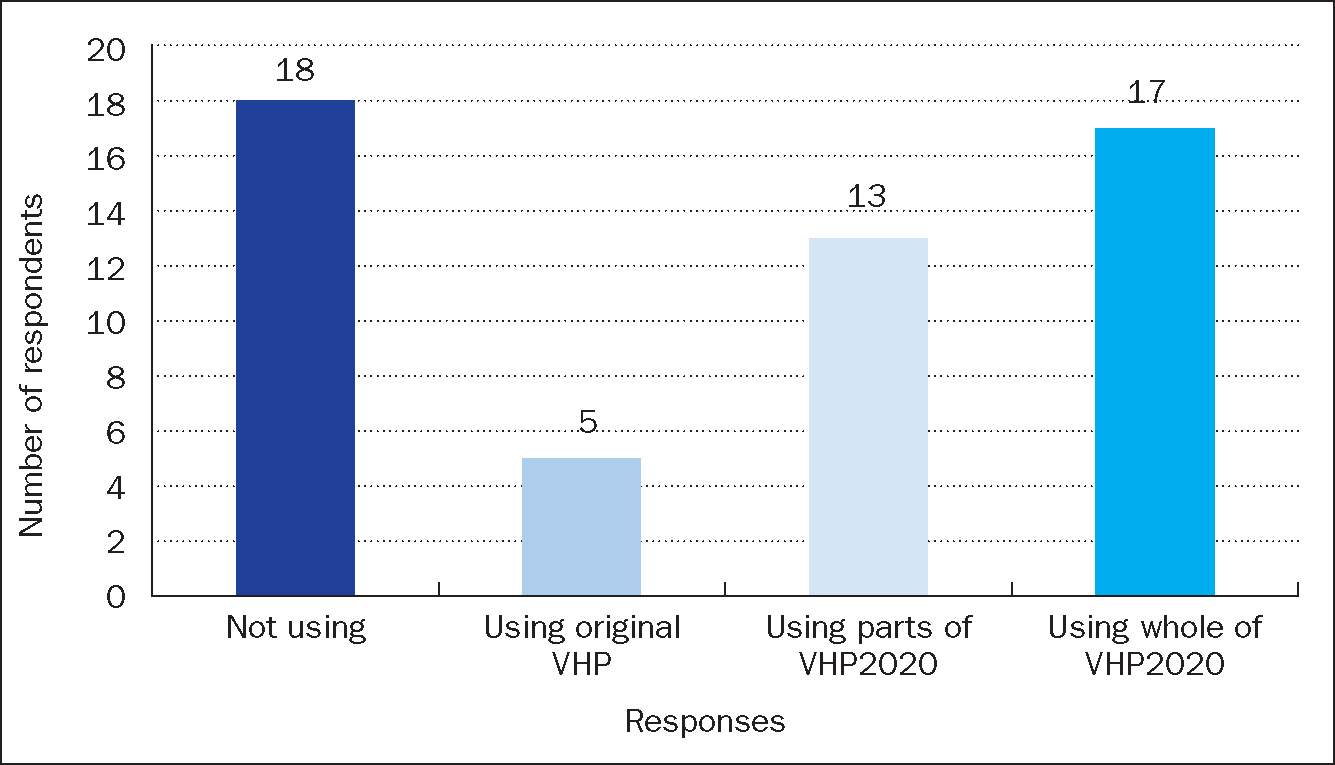

Thirty respondents were using the updatedVHP2020 with the majority of these being based in England (73%, n=22) and working as vascular access specialists (73%, n=22). When asked how they were using the VHP2020, 17 (57%) were using the whole updated framework, and 13 (43%) were using one or more sections (Figure 3). The most used sections were ‘The right line decision tool’ and ‘The peripheral vein assessment’ to support vascular device choice and peripheral vein assessment. When considering where the respondents were using the VHP2020, 63% (n =19/30) were using it within an IV team, with the next most common response being the whole hospital. The main context for using theVHP2020 was to support decision making for VAD selection (87%, n=26/30).

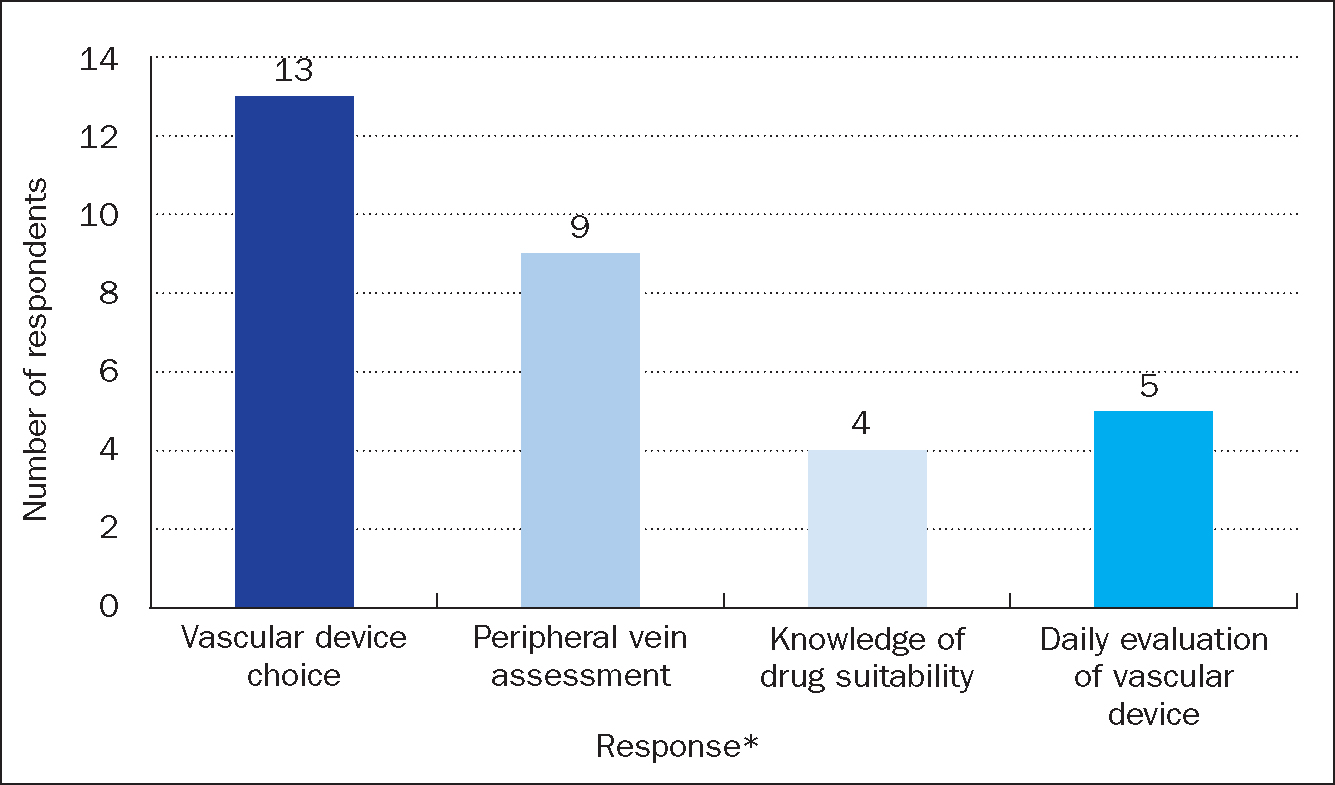

Those using theVHP2020 in sections mainly reported doing so to improve VAD choice (100%, n =13) and peripheral vein assessment (69%, n=9; Figure 4). Respondents were asked to specify which sections of the VHP2020 they were using to improve practice. Eight provided responses.‘The right line decision making’ section was stated in 88% (n=7) of responses, followed by 50% (n=4) using the ‘Peripheral vein assessment’ section. The ‘Daily evaluation’ section and ‘Suitability of medicines’ section were both mentioned once.

Respondents were asked about the context and departments where the framework is being used to understand its implementation (Table 1 and Table 2). Two counts of missing data were reported from those using the whole framework for these questions (n=2/17), giving 28 respondents.

Table 1. The context in which the VHP2020 is used

| Context for use | Whole VHP (n=15) | One or more sections (n=13) | Overall (n=28) |

|---|---|---|---|

| To support decision making for vascular access device selection | 14 | 12 | 26 |

| For education and training programmes | 8 | 10 | 18 |

| Assessing IV team and service needs | 9 | 4 | 13 |

| Business care development | 4 | 1 | 5 |

VHP2020=UK Vessel Health Preservation Framework 2020

Table 2. Departments using the updated VHP2020 framework

| Department | Whole VHP2020 (n=15) | One or more sections (n=13) | Overall (n=28) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole hospital | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| IV team | 10 | 9 | 19 |

| Chemotherapy | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| OPAT | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Other | 3 | 2 | 5 |

OPAT=outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy; VHP2020=UK Vessel Health Preservation Framework 2020

The primary context in which theVHP2020 was used was to support decision making for VAD selection (93%, n=26/28). This was followed by use in education and training programmes (64%, n =18/28). The VHP2020 was less frequently used for business care development (18%, n=5). The IV team was the main department using theVHP2020 (68%, n =19/28). In seven instances (25%) where the whole hospital was using the updated VHP2020, four were using the whole framework, and three in part.

The three ‘other’ departments using the framework in part were the vascular access team, educators (two respondents), and neurosurgery. There was one instance where ‘other’ was selected but the department was not reported.

The final aspect of the survey asked respondents to evaluate the use of theVHP2020 using free-text responses. These questions were presented in two sections, one exploring the perceived benefits and one the reported drawbacks of use of theVHP2020. The benefits reported were grouped into three categories:

- Decision making

- Policy and guidance

- Better care.

The most common benefit of the VHP2020 documented by 11 out of 17 respondents was decision making. Specifications of decisions made related to infection control, VAD choice, and right line at the right time. Five commented on the benefit of theVHP2020 in standardising the care and guidance provided by defining terms, bringing structure to decision making, and enabling safe use of devices. Four respondents identified beneficial outcomes ofVHP2020 use, which were centred around the provision of better care.

The drawbacks reported were grouped into two main categories:

- Accessibility of use

- Complexity and length.

Five respondents reported no drawbacks to use, and two reported potential improvements rather than specifying drawbacks. Accessibility of use (n=6) referred to use of the framework, with respondents noting the prescriptive, specialised nature of the tool, which may make it less accessible for non-vascular access specialists. Drawbacks referring to the complexity and length of theVHP2020 came from those using parts of the framework (n=5), who commented that it can be difficult to follow. Two suggested potential improvements, one commented that having a paediatric-specific framework would be beneficial as they currently must adapt the framework for use with this population. Another commented that a ‘drop-down interactive app’ would benefit the framework.

Discussion

The number of responses was disappointing, with a much lower response of 88 compared with 270 respondents on the evaluation of the original VHP framework in 2016 (Burnett et al, 2018). This may have been due in part to the work pressures being experienced by NHS staff because of the impact of COVID-19 across healthcare services at the time of the survey. In addition, the survey carried out in 2016 offered an incentive through the opportunity of winning a gift voucher (Burnett et al, 2018), which the later survey did not.

A notable area of concern was that 24% of the respondents who were aware of VHP had not heard of the updatedVHP2020, highlighting the need to find effective methods to reach the target audience. The national restrictions to control COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021 resulted in face-to-face meetings, symposiums and conferences not taking place, this reduced the opportunities for sharing theVHP2020 more widely. Communication via the NIVAS membership was found to be the most effective method of informing the target audience. Word of mouth was also noted as a way of informing health professionals of the VHP2020, with 21% of respondents being informed by a work colleague. Conferences and study days were cited as the most popular methods of communication for the original VHP framework (Burnett et al, 2018).

Limitations

The limitations of this survey are mainly due to the low number of responses, making it difficult to fully understand how widespread the use of theVHP2020 is and to what extent practitioners are seeing the benefits and drawbacks of its use.

Conclusion

Respondents to the survey made positive comments on the use of the VHP2020 in helping them to provide better care, enabling safe use of devices, defining terms, standardising care and guidance and guiding VAD choice. More positive feedback was given compared to negative feedback. Negative feedback included a small number of responses referring to the complexity and length of the VHP2020. Further work is needed to inform health professionals about theVHP2020, which appears to benefit patients in terms of device choice and patient safety.

KEY POINTS

- The main reason why respondents are using the UK Vessel Health and Preservation Framework 2020 (VHP2020) is to support decision making for vascular access device selection

- The VHP2020 can be used as a whole framework or in sections

- Further work is needed to ensure the VHP2020 reaches all practitioners performing vascular access

- Those using the VHP2020 found it has more benefits than drawbacks

CPD reflective questions

- How do/would you use the VHP2020 framework to assist with vascular access device decision making in your clinical area?

- What are the implications for poor vascular access device choice?

- What are/would be the benefits to your patients of using the VHP2020 framework in your clinical area?